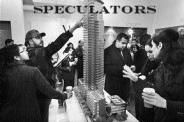

Brace yourself. On first reading Froogle’s latest episode, I found myself on more than one occasion spontaneously exclaiming out loud, or grimacing & ducking, or writhing in vicariously experienced psychic pain.

Boy, these guys went through a lot.

First thought: The vast majority of people that I know, myself included, are completely incapable of doing what Froogle and his wife did here. Their industry is remarkable, to do so much themselves, to be so thoroughly involved in the whole process.

Most mortal Vancouverites: “I notice a photo is hanging skew, I rise from the sofa and straighten it.”

Froogle Scott: “I rent a large rotary hammer drill to drill one-inch diameter holes fourteen inches deep in the concrete foundation walls.”

The result, of course, is that Froogle has ended up with a house where his sweat is quite literally part of the foundations, and that in itself is a unique reward.

Second thought: Froogle’s story is of a very, very diligent, meticulous, and industrious couple riding shotgun on the renovation of their house. One is amazed by the number of serious deficiencies they discovered in doing so. It leads us to consider how many homes in Vancouver have substandard, shoddy, or even dangerous construction because they were built for clients who were not watching as closely. Is such construction the norm rather than the exception?

Third thought: By their estimation, Froogle and his wife got their renos done at fair prices, in ‘Vancouver terms’. Yet the numbers are still eye-popping. The story makes one consider how the construction industry in this city has become a hyper-efficient machine for extracting money from the banks of homeowners. This process has worked superbly up until now because homeowners always ‘knew’ that the projected future value of their house merited the renovation expenses. And there was also the additional perception of this all being somehow prudent, of it representing an ‘investment’ in one’s house (and by extension, in oneself). What could be more sensible? Use the house’s increasing value as a tool to improve itself! It seems so symmetrical, so right. This all made spending on renos that much easier.

Froogle (e08): “I’m secretly horrified. I can’t believe the size of the cheques we’re writing against our home equity line of credit. I’ve never seen or written cheques this large, with this frequency, in my life.”

Contractor (e07): “That’s what things cost now. The cost of everything is through the roof. Skilled trades are through the roof. But look at what you’re sitting on. You’re sitting on a property that’s probably going to be a million dollars in a few years.”

As a result, Billions of borrowed dollars have been injected into our local economy over the last ten years. It looked fine from the outside while the process continued. Now the money has been spent, but the debt remains.

Regardless of how the whole boom plays out, we’ll all remain indebted to Froogle for sharing his remarkable story.

As I said, brace yourself… – vreaa

Froogle and Froogletta Scott

Froogle and Froogletta Scott

Part 8: Renovation Nervosa Finale

Recap

Late November 2007. After fifteen months, our renovation has evolved from a start-and-stop, homeowner-managed undertaking into a bigger, more complex, increasingly expensive project run by a general contractor. The initial negotiation with Nick Costa, the general contractor, was a month of back and forth, during which Nick was difficult to pin down on numbers. Our subsequent reference check was more cursory than it should have been. My wife and I have some misgivings about hiring Nick, but we’ve put ourselves in a difficult position. Or, to be more accurate, I’ve put us in a difficult position by underestimating the scope of the work, and by overestimating how much of it we can reasonably achieve or contract ourselves, while still adhering to my ambitious vision for the renovation — all of this during a construction boom that makes finding and hiring contractors and tradespeople unusually difficult. With winter now upon us, we’re without a furnace, without insulation in the gutted bottom half of the house, and without a laundry. We give Nick an initial deposit of $20,000 on a $100,000 contract. We’ve spent an additional $40,000 on work outside the contract with Nick, so it looks like our initial estimate of a $100,000 total price tag is out the window.

We may have had our first encounter with the underground economy, when two young, inexperienced workers remove the masonry flue in the center of the house. We’ve had our first deficiency, when Dylan, Nick’s lead carpenter on our job, somehow forgets to install a strip of sill gasket between the bottom of the new central supporting wall and the new concrete footing. We’ve experienced our first attempted gouging — or at least, what feels like gouging — when Nick presents us with an add-on quote of $11,000 to remove the old basement slab and excavate a foot of brown soil beneath it, a job that has to be completed before any other aspect of the renovation can proceed. Eventually, we’re able to do the job for $3400 when we succeed in hiring Delmore, a concrete demolition contractor who uses a remote-controlled micro excavator to do the work. We’ve had our first casualty, when Leonard, the handyman we’d initially hired to help with the project, quits in anger, feeling we’ve usurped his role by bringing in Nick.

We’re learning about renovation and construction the hard way, and even harder lessons are still to come.

A disagreement, and more research

I call up the company that redid the drain tile the previous year and have them lay some more drain tile either side of the central footing, where water is collecting in the trench, and tie in the new pipe to the existing system around the outside of the house. As part of his contract, Nick brings in a plumbing company to replace the bottom half of the sewer stack, and rough in all the plumbing drains that will run beneath the new basement slab. Once the black ABS drain pipe is in place on top of the brown soil, the concrete crew is free to start work on the new slab. They’ll begin by laying in six inches of drainage gravel, which will allow sub-surface water to rise and fall without becoming trapped in soil immediately beneath the slab — the issue with the old slab. Pink styrofoam insulating board (R-10) will go on top of the gravel, with a poly vapour barrier on top of the insulation. Rebar, wired together into a mesh, and elevated a couple of inches, will sit on top of the vapour barrier. Four inches of concrete will then be poured, encasing the rebar and forming the new basement slab.

(Additional drain tile: $1166)

Excavated basement with section of plumbing drain

Excavated basement with section of plumbing drain

Nick and I disagree about the value of the styrofoam insulation beneath the slab. He thinks it won’t do anything, that “the ground is a natural insulator,” and the additional $1500 to install the styrofoam is a waste of money. Marco, the lead on the concrete crew, is adamant that slab insulation does cut the chill that occupants feel under their feet, but leaves the decision up to us.

The discussion goes around in circles for a few days. I find plenty of personal opinion on the Web arguing in favour of the insulation from both a comfort and energy-savings standpoint, but given Nick’s strong opinion to the contrary, I feel I need something a bit more solid before making a recommendation to my wife. I get back to my familiar 5:00 a.m. routine of scouring the Web for information. I’m becoming a little sick of conflicting opinion, and the difficulty of getting a straight answer, and the need to do panicky research under the gun. It takes a few frustrating mornings to find what I’m looking for, but then I do: a CMHC research bulletin that reports on actual tests done with temperature sensors “aligned vertically to measure the thermal gradient from the top of the slab through the insulation and into the soil below.” In a house with no slab insulation, the temperature just below the surface of the slab is only slightly higher than the temperature of the soil, and several degrees cooler than the air temperature in the basement. In a house with two inches of styrofoam insulation beneath the slab, the slab temperature is almost identical to the air temperature, and significantly warmer than the soil temperature. I report my findings to my wife, and tell Marco we’ll be going ahead with the insulation. It’s only a couple of weeks later, during one of my increasingly frequent calls to the building inspector, that I discover the current building code actually requires a minimum of two feet of rigid insulation running either horizontally or vertically at the perimeter of the slab. “To provide a thermal break,” the inspector tells me.

Hellhole

We discuss with Marco the band of soil that Delmore left at the base of the foundation walls as a precaution. Because the walls have no footing — they just end, not even resting on hardpan, but on the brown soil above — Delmore was reluctant to remove the last of the soil sitting against the walls too far in advance of the new slab being installed. Now that the concrete crew is nearly ready to go, the soil has to come out. We’ve kept a roll-off container for this purpose, and on the first weekend of December my wife and I get out the shovels and the wheelbarrow and go to work excavating the last of the soil in “the hellhole,” as we’ve taken to calling the basement.

It just happens that, weather-wise, this weekend is one of the most miserable of the year. We’ve been living without a furnace since April, and over the last month surviving off space heaters. We eventually borrow a good quality, oil-filled radiator from one of my wife’s brothers, which improves the heat situation to the point of being somewhat tolerable, but that’s after the weekend in question.

We work our way slowly around the perimeter of the basement, loading the moist, dense soil into the wheelbarrow. When the wheelbarrow is two-thirds full I run it up a plank at the back door, and around the house to the street, where I run it up another plank and dump it over the edge of the container. As I do this, heavy, wet snow falls from a sky the colour of sludge. The snow glops down on my toque and wool jacket, melting almost immediately and progressively working its way through multiple layers of clothing. Over and over we repeat the routine of loading and dumping the wheelbarrow, the volume of soil in the narrow band at the wall greater than we anticipated. I realize what a disaster it would have been to have attempted excavating the entire basement by hand. As we tread back and forth across the exposed soil in the basement it becomes mucky, water from days of rain forced up by the weight of our boots. We both feel murderous.

Soil dumped in the container

Soil dumped in the container

We finish sometime in the pre-dark of late afternoon, and retreat upstairs to hot showers — our one remaining creature comfort. I’m completely sodden, my clothes grimy with mud. After showering, we sit on the couch, both of us wearing thick sweaters and toques and wrapped in blankets, the hockey game turned up over the noise from a space heater, while we drink red wine to try to stay warm.

My jeans, post-hellhole

My jeans, post-hellhole

Dodging one bullet, getting hit by another

A problem arises — a significant one. The building inspector comes for a look and discovers that the foundation walls lack a footing, and don’t even extend down to the hardpan. Even though we’ve got the new central footing, which now provides excellent structural support to the center of the house, the inspector is worried that the house could subside around the perimeter, especially now that we’ve excavated the soil away from the interior of the foundation walls. He speculates that we may have to underpin the foundation walls by installing proper footings beneath them.

Underpinning would be difficult and costly, and time-consuming, because excavating beneath the walls to make space for footings could only be done in short sections at a time, to avoid the danger of collapsing a wall. Even for a small house like ours, underpinning could easily add $30,000 or more, and six weeks, to the reno. It would also risk disturbing the new drain tile around the perimeter of the house. Marco says they could do the underpinning, but shakes his head, his demeanour dark. “It would be a nightmare.” For that much extra expense and effort, it would make more sense to just raise the house and completely replace the old foundation. I point out to the inspector that the house hasn’t budged in 60 years, and that the structural engineer, when I asked him, said the same thing and wasn’t worried about the walls. The inspector isn’t convinced. The structural engineering drawings contain no details related to the walls. He tells us that the structural engineer will have to provide a revision that specifically addresses the walls, and sign off on their adequateness, before he’s willing to let work proceed.

I give TK (Tony Kwan), the structural engineer, a call and explain the situation. A lot rides on TK’s willingness to put his professional seal on what he’d previously stated only informally. I’m careful to hide my trepidation. We’ve come to understand that TK likes to make money, and if he smells fear he’ll no doubt sense an opportunity to extort more from us. So instead of asking, I tell him in a friendly and neutral manner that he needs to provide a revision, while subtly suggesting there was an oversight on the original drawings. And we need the revision right away. I’m relieved that he seems more interested in dismissing the inspector’s objections than in asking any further questions.

“The house been there 60 years. Your house is light, it’s all 2×4.” Then he stops himself, and briefly switches to his slower, more probing manner. “You guys going to add a second storey?”

I already know the answer to this question. “No.”

“Okay.” Switching back to Napoleonic mode. “I can do a letter. But no second storey. That might be too much weight.” No mention of any additional fee.

“Okay,” I reply. No problem at all. The disappointment at losing the option of a second storey — something I had been thinking about as a future possibility — is more than offset by vanquishing the spectre of underpinning.

A few days later I give the inspector a copy of TK’s letter, which states that underpinning is not required if there is no additional loading on the foundation walls. The letter will be kept on file at City Hall. The inspector somewhat begrudgingly approves a continuation of the work. At Marco’s suggestion, we also decide that the ends of the rebar forming the mesh that will reinforce the slab should be doweled into the foundation walls, providing a strong connection between the slab and the walls, and giving the walls some additional support. Doweling involves drilling a hole horizontally into the wall for each length of rebar, and anchoring the end of the rebar in the hole with construction epoxy. There will be a piece of rebar doweled every 18 inches on all four walls, so the dowelling represents a considerable additional expense, mostly because of the labour.

TK isn’t done with us, however. The following week Marco and his crew lay in and compact the drainage gravel, install the layer of styrofoam insulation, lay down the vapour barrier, and begin dowelling the rebar and wiring it together into a mesh. I phone TK to arrange an inspection. Both TK and the building inspector have to sign off on all the preparatory work before the concrete can be poured. TK asks what stage the work is at. I tell him the crew is well into dowelling and wiring the rebar. He asks me how thick the rebar is.

“10M,” I reply. 10M is about half an inch in diameter.

“What! 10M? Nobody uses 10M.”

“What do you mean?” Slab rebar isn’t even specified on TK’s drawings, and my understanding has always been that it’s optional. A good idea, but optional.

“It has to be minimum 15M. I won’t approve 10M.” 15M is about five-eighths of an inch in diameter.

A hurried round of phone calls ensues. From work, I phone Marco at the house and give him the news.

“What! That’s crazy. We’re three-quarters done. He’s crazy! This slab is already so overbuilt it’s ridiculous.”

Marco phones TK, and then phones me back at work. “Well, I talked to him and he’s not budging, at least until he comes for a look. It’s ridiculous.” By ‘a look’, I’m assuming TK means a site visit, each of which costs $250. And he’s unwilling to come the same day, claiming to be booked solid, even though he’s at his office, and his office is a five-minute drive from the house. “We’re going to have to pull out,” Marco says. “And it’s too late in the day to go to another site, so unfortunately I’m going to have to charge you for the lost time.” There’s not much I can say. The lost time ends up as an extra $400 on Marco’s next invoice. That evening, when I relay the latest developments, my wife is furious. From growing up in the local Chinese community, there’s something she recognizes in TK, and it’s not something she likes.

The next day the crisis resolves itself with some soothing talk from Marco, and some extra lubrication from our spiraling line of credit. TK agrees to a doubling up of the 10M rebar — a length of rebar doweled into the walls every 9 inches instead of every 18. This of course doubles the cost of the rebar work, but it’s cheaper than ripping everything out and starting again with 15M bar. Marco considers the whole thing lunacy. And TK gets to bill for an additional site visit.

(Slab preparation work: $6400)

(Additional rebar work: $2700)

Completed slab preparation work

Completed slab preparation work

Slicing concrete

One final job must be completed before the pouring of the slab can go ahead. I bring in a concrete cutting and coring company to cut an access door in the side wall of the concrete stairs on the front of the house, and to make a few other minor cuts in the foundation at other locations. Nick has recommended that we modify the layout of the rental suite by locating the new furnace and the hot water tank in the space under the stairs, rather than use precious square footage in the suite for a mechanical room. We like the suggestion and agree to it. Currently there is no wall between the space under the stairs and the interior of the basement because the original sheathing and studs, exposed to the humid soil under the stairs in the inadequately ventilated space, rotted away. Once a new concrete floor is poured under the stairs, and the wall is rebuilt, we’ll need the exterior access door to get at the mechanicals.

A worker shows up with a specialized concrete saw that has a circular blade about three feet across. He attaches the saw to the side wall of the stairs. The saw uses a wet cutting system, which sprays water over the blade as it cuts. The blade goes through the concrete like butter, and leaves a horrendous, gooey grey mess in its wake.

(Concrete cutting: $835)

Promise and possibility

The concrete crew pours the new slab on January 2, 2008 — the first working day of the new year. In the half dark of early morning the bulk of a concrete truck and a pump truck fill the back lane behind the house. The workers run a hose from the hopper at the rear of the pump truck into the basement. Once everyone is in place, the driver starts pumping the concrete. The crew moves quickly, one worker holding the end of the hose as the grey mix shoots out, Marco and the others spreading the mix with wide concrete rakes and trowels.

Pouring the slab

Pouring the slab

A few days later, my wife and I stand on the new slab. We feel we’ve reached a major milestone. The hellhole is no more. We stand in one corner of the basement, a smooth and beautiful expanse of new concrete stretching out before us, almost like the new year itself, full of promise and possibility. It’s been a grinding, stressful, sometimes brutal sixteen months to get to this point, but now we’re here and I feel that the worst is behind us. We’ve got a new, solid, clean, dry foundation upon which to build.

In a normal world, with normal people, that could very well have been the case. But Vancouver in early 2008 is not a normal world. It’s one in which people like TK and Nick Costa can operate and thrive. We just don’t know that yet.

(Slab pour: $7450)

The new slab

The new slab

Shit

What follows is six months of shit. As a one-word summary of the Nick Costa experience, a little crude perhaps, but the most fitting.

There’s so much to choose from, I’m going to be selective and present just the most egregious incidents.

Dylan’s split personality

The flush beam and the joists. The amount of woe surrounding this portion of the construction is almost laughable — if it weren’t the key structural support for the center of the house.

As part of the new central supporting wall, Dylan and an assistant have installed a flush beam to create a seven-foot-wide opening that will eventually serve as the entranceway into the living room and kitchen. The ends of the floor joists at the center of the house rest on top of the new supporting wall, except in the area of the flush beam, where they are attached to the side of the beam with joist hangers.

At several points in this episode I’m going to be referring to this beam, the joists connected to the beam, and the joist hangers, so to help with visualizing this construction detail, I’ve included the picture below which illustrates using a joist hanger to attach a joist to the side of a beam.

Joist hanger used to attach a joist to the side of a beam

Joist hanger used to attach a joist to the side of a beam

On one side of the beam, a headroom problem reemerges. Nick wants to run a single main trunk for the new heating duct system down the center of the suite, rather than split the main trunk into two parallel trunks running along the ceiling at the outer walls. Regardless of where the main trunk or trunks are located, it will involve running bulky, rectangular duct immediately below the joists. The duct will then be boxed in with drywall, creating what is called ‘a drop’. Drops are the often unsightly boxy structures typical of low headroom basement suites. They cover the various structural and mechanical components like beams, heating ducts, and pipes that run overhead. In full height basements, all this infrastructure can be gracefully hidden above a dropped ceiling, but we don’t have enough headroom to do that. Done badly, drops look terrible, and scream basement suite. Nick’s rationale is that walking under a drop incorporating both the beam and the main heating trunk at the central location will be far less noticeable than walking into an open concept living room and kitchen and having your eye drawn to a boxy drop running the length of the outer wall. My wife and I agree.

Unfortunately, the minimum vertical dimension for the main heating trunk, as specified by the heating company, is five inches. Add another inch for the drywall below the trunk line, and a slight gap between the two, and we now have a structure that extends an inch and a half below the city’s specified minimum headroom of 6’6” over 80% of the suite area and all exit routes. Nick’s solution is to cut a long, shallow notch out of the underside of each joist on one side of the beam so that in this area the trunk line can be moved up enough to meet the city’s headroom requirements. Cutting notches out of joists is dicey, given that they’re the structural members supporting the floor above — especially joists that are only 2×8 to begin with, rather than the 2×10 or 2×12 used in modern residential construction. Nick consults TK, who says that if we double up the joists by adding a new joist to each of the existing joists in the affected area, he will authorize a notch two feet long by one-and-a-half inches deep, and no more, in each joist pair. Everyone agrees on this plan of action.

Dylan does the work. When I get home and go downstairs to inspect, I’m dumbfounded. Dylan has doubled up the joists correctly, pre-cutting the required notches in the new joists, but in the existing joists he’s made a one-and-a-half inch vertical cut, then attempted to split out the notches horizontally. The result is atrocious. The splits are not a straight horizontal line, but instead veer all over the place, resulting in much more than one-and-a-half inches of material being removed from each joist, seriously undermining their structural integrity. And he didn’t do it with just one joist, realize that method was a failure, and then revert to the more time-consuming but proper method of making the horizontal cuts with a circular saw, finishing with a handsaw or a reciprocating saw those areas that couldn’t be reached with a circular blade. No, he mangled each existing joist in the same utterly moronic manner. There’s no way TK or the city inspector is going to approve this. There’s no way I’m going to approve it.

Here’s a picture of the beam and the attached joists. You can see just how much additional material the splitting removed by comparing the split joists to the pre-cut joists installed beside them, and by looking at the thickness of the little blocks of wood Dylan had to insert in the bottom of the joist hangers to allow the split joists to rest on something.

Split joists paired with pre-cut joists

Split joists paired with pre-cut joists

I’m displeased. I phone Nick. He comes over. He admits that Dylan’s work is “a bit rough,” but doesn’t seem overly concerned. I tell him that we’re going to need to get TK back to assess the situation. If I had the experience then that I have now, I would have thrown Nick and Dylan out on their asses that very day. TK comes for a look later in the week and pronounces. The joists in question will now have to be tripled up with the addition of a third, properly notched joist added to each existing joist pair.

Drip, drip, drip

At Nick’s suggestion, we’ve decided to locate the new furnace and the hot water tank in the space under the concrete front stairs. In these little East Vancouver houses, reclaiming some additional square footage is always welcome. We’ve had Marco and his crew install a vapour barrier and a new concrete floor in what will become the mechanical room.

As the concrete floor cures I notice drops of water suspended from the sloping underside of the stairs, and dark patches on the new concrete floor. I assume that the water vapour given off by the concrete during the curing process is rising up and condensing on the cold concrete surface above. Eventually everything dries out and the space looks good. Because we’re adding the space under the stairs to the usable square footage of the house, the inspector requires that we insulate it, either with standard frame walls and fiberglass batt insulation, or spray-on foam insulation.

I’m down in the basement a few days later and have another one of those nasty renovation surprises. Drops of water are again suspended from the underside of the stairs, and new dark patches have appeared on the floor, beneath the drops. I watch as a couple of drops fall and are absorbed into the dark patches. It’s been raining for the last couple of days. I surmise that the drops aren’t condensation from the curing concrete, but rather rainwater making its way through the old concrete of the stairs.

More frantic research. Guess what? Concrete is porous. Between the grains of sand and cement that form the basis of concrete are thousands of tiny capillaries that water just loves to flow along. In fact, a phenomenon called ‘capillary attraction’ means that concrete acts like a giant sponge. In our case, the sponge is probably becoming saturated after a couple of days of rain hitting the top side of the stairs, and is shedding the excess water into the space below.

The amount of water isn’t huge, so I’m still holding out a shred of hope that it might only be condensation. The sun returns, and the space dries up. I get out the garden hose, position it outside the front door, and point it over the lip of the top step. I turn on the water and watch as it cascades down the stairs to the front walkway. Satisfied that this amount of water approximates a Vancouver monsoon, I go back inside the basement and look into the space under the stairs. Bloody Niagara Falls. So many drops of water that they’re forming into sheets and spilling down on the floor. I go back outside, turn off the water, and do a fair bit of swearing.

The space beneath the stairs

The space beneath the stairs

Solution time again. There’s no way we can install a new, $10,000, high-efficiency gas furnace and the hot water tank in this space until we’ve made it waterproof. It occurs to me that Nick, as a general contractor selling construction expertise, should have foreseen this possibility. Why had it been left up to the homeowner to discover the problem?

Despite the setback, we decide to persevere with the plan to locate the mechanical room under the stairs. Reincorporating the mechanical room in the suite layout would mean sacrificing the one decent storage room we’ll have, or changing from a two bedroom to a one bedroom unit, which would significantly impact the amount of rent we’ll be able to charge.

Nick’s solution is to paint the stairs with waterproof paint. Won’t the paint progressively wear off in the traffic areas? I ask. Sure, Nick replies, but you can just repaint when that starts to happen. I tell him that I’m going to explore other solutions. The problem with the stairs completely messes up the heating company’s schedule. They had been on the verge of installing the new furnace and duct system. The custom ductwork is sitting in their warehouse, ready to go. Now they’re on hold until we find an acceptable solution. My wife and I, looking forward to the resumption of heat, continue to freeze and huddle around space heaters.

One option is to get Delmore back, demolish the concrete stairs, and rebuild them with frame construction and plywood sheathing, including a waterproof, torch-on membrane immediately below the treads and risers of the stairs. We’d probably be able to save the new concrete floor, but the new drain tile, which runs around the perimeter of the stairs, would likely get disrupted as part of pouring new footings for the wood frame walls. It all sounds expensive and time consuming.

What we try first is a cementitious waterproofing compound that when applied grows microcrystals within the tiny capillaries of the concrete, progressively blocking them — or so the marketing literature states. The more water seeping through the untreated concrete, the better, because the crystals are water activated. A contractor shows up and applies the compound to the underside of the stairs — roof and walls. After a few days, the amount of water working its way through the stairs is significantly reduced, but not halted completely. I phone the contractor and tell him we still have a small, wet area on the underside of the stairs. He returns, applies more of the compound, which improves the situation further, but still a small amount of water is seeping through. And anything less than an absolute seal is no good. When I mention to TK the approach we’re taking he dismisses it. “That stuff’s no good for old concrete. It only works on new concrete.” I ask his advice and he suggests torch-on, or some other kind of waterproof membrane, beneath a protective cladding like tiles.

(Concrete waterproofing compound: $1000)

The stairs have now become a project within a project. With the addition of the concrete floor, the cutting of the access door, and the application of the waterproofing compound, we’ve dumped in enough money to this one piece of infrastructure that changing course and demolishing the stairs would be painful. We decide to persevere and my wife takes on the responsibility of finding a decent tiling company.

Short people

Dylan is tall, definitely over six feet, but he comes perilously close to joining Randy Newman’s ranks of short people (“Short people got no reason / To live. / They got little hands / Little eyes…”).

The joists in one corner of the basement need to be doubled up. This corner is where the stairs between the two levels of the house used to be located before they were removed, probably by the Portuguese brothers when they converted the bottom half of the house to a rental suite. When they closed up the opening between the two floors, they used joists that weren’t quite long enough to span the distance from the top of the outer wall to the top of the old central beam. The joists were probably scavenged from somewhere, and they got them cheap, or for free. Unfortunately, they were about six inches too short for their required purpose. To make them work, they had to run a horizontal 2×4 ledger under the joists at either end. One ledger was nailed to the side of the old central beam, and the other was nailed to the side of the double top plate — the stacked 2x4s — on the outer wall. The joist ends rested on top of these two ledger boards — an adequate solution from a structural standpoint, but an unsightly one because at the ceiling line the 2×4 ledgers stuck out from the wall and the beam. When Dylan replaced the central beam with the new central supporting wall he reattached the ledger as a temporary measure until the short joists could be paired with new, longer joists that would run from the top of the outer wall to the top of the central wall. Removing and reattaching the ledger at the central location had not been a problem because the temporary supporting walls were in place at the time, taking the weight of the joists overhead and the floor above.

The ledger at the outside wall is a different matter. Directly above it, in a storage room on the main level of the house, are two large, old-style, green metal file cabinets fully loaded with papers. A combined weight of probably a thousand pounds.

While discussing this portion of the framing with Nick I tell him about the file cabinets and offer to unload them and move them to another location upstairs. He tells me not to worry about it. They’ll install some temporary supports below the joists when the time comes to do this portion of the job. When that day draws close I remind Nick about the file cabinets and he again says not to worry. The day before Dylan is going to do the work, I tell him directly about the file cabinets and how heavy they are.

When I get home at the end of the day, the new joists are in place, paired with the short joists. But on the phone with Nick later that evening he reveals there had been a little mishap. (Why he tells me, I have no idea.) Somehow Dylan and Nick, who was there at the time, forgot about the file cabinets, or worse, are beginning to reveal intellectual challenges around subjects such as gravity, and physical properties like weight, and the load-bearing capacity of unsupported horizontal framing members. According to Nick, the instant that Dylan, standing directly beneath perhaps half a ton of loaded file cabinets, pried the ledger board from the outer wall all the joist ends in the area, with a horrendous noise, collapsed straight down about six inches, which would have put them close to the top of Dylan’s head. Nick grabbed a 2×4 stud and rushed over, and between the two of them they were just able to wedge the stud beneath one of the joists, and then quickly do the same with the other joists, preventing what might have been a total collapse, two smashed file cabinets sitting in the basement, a cracked basement slab, and a destroyed storage room floor. As it is, the storage room floor still isn’t quite right, feeling spongy and creaky underfoot, probably from the plywood subfloor being deflected and perhaps partially splintered when it was bent down by the weight of the file cabinets.

No doubt many of you have heard of the Darwin Awards. From the Darwin Awards web site: “In honor of Charles Darwin, the Darwin Awards commemorate those who improve our gene pool by (accidentally) removing themselves from it. The Award is generally bestowed posthumously.”

I’d say Dylan, aided and abetted by Nick, narrowly avoided becoming a recipient.

Once again, why?

In the previous episode, in reference to our eventual decision to hire Nick, I asked the question Why? I ask the question again, now in reference to continuing the relationship, as some of you are probably wondering why we allowed this circus to go on as long as we did. (Although, as a reminder, I have focused on the most egregious incidents, which has the effect of amplifying the horror.)

The short answer to Why? is that we don’t allow it to go on for very long. Although we hired Nick at the end of October, with the exception of the central supporting wall, his company doesn’t begin to do much work until early January 2008. On the last day of February, just eight weeks later, I phone Nick and tell him we don’t want to continue with the contract. Which is a polite way of saying, “You’re fired.” To which Nick casually responds, “Okay.”

The slightly longer answer is that we are quickly unhappy with Nick once work starts in earnest, and confront him on several occasions about the sources of our unhappiness. Workers absent for days with no prior warning, and lame subsequent excuses from Nick. Multiple blown appointments when Nick is “coming over in an hour,” then fails to show. Multiple breaches of the building code, including a single top plate rather than the required double top plate on the central supporting wall, and the attempt, which I quickly stop, to put vapour barrier directly against the concrete foundation wall, creating the perfect conditions for mould, rather than on the warm side of the new framing. Overall poor quality of framing. Nick’s demand for an early second draw — another $20,000 well in advance of the contractually-agreed-upon milestone, which is completion of the framing and the plumbing and electrical rough-ins.

Because of the overall slow pace, and the worker absences, we aren’t even close to reaching the milestone. I tell Nick flatly, “We aren’t giving you any more money. You need to reach the milestone, and the work has to be passed by the structural engineer and the various city inspectors before we’ll release any more money.” The real reason for the worker absences, I find out from Dylan and the other carpenter, is greed. Nick has eight different jobs of various sizes on the go, and five workers. This from a guy who solemnly stated he would never max himself out. Workers are continually being yanked off one job and sent to another — probably to whichever client is currently complaining the loudest — and as a result spend half their day driving around town.

There’s more, but that’s probably enough. However — in this slightly longer answer to Why? — through it all, Nick never stops being responsive. He’s a master at appearing at the precise moment my wife and I agree we’ve finally had it. Of somehow diminishing our grievances to minor hiccups, of displaying just enough construction expertise to make us think twice about giving him the bum’s rush. He has the con man’s silver tongue. But that’s not quite right. I google “con man’s silver tongue” to check my use of “silver tongue” in the context of con men, and discover The Ten Commandments of Con Artists, a list of con artist best practices attributed to a renowned, early-twentieth-century con man, Victor Lustig. Commandment #1 leaps out at me: “Be a good listener — the myth of the fast talking, silver tongued con man should be ignored.” In the previous episode, weeks before reading Lustig’s commandments, here are the first two sentences I wrote describing Nick: The following week I meet Nick Costa, the general contractor, for the first time. My initial impression is that he’s a good listener.

A shoelace snaps

A specific incident leads to firing Nick. It’s a relatively minor incident, but indicative of the core problem — and also the last straw.

As another way of conserving as much space as possible in the suite, we’ve decided that instead of swing doors, we’ll use pocket doors throughout. Pocket doors slide back and forth on an overhead track that runs above the doorway and inside the adjacent wall, thus requiring no additional space to open the door, unlike the common swing door which requires swing space into a room.

As part of framing the new suite, Dylan and another carpenter install a number of pocket door frames — prefabricated units that include a door frame and an adjoining section of wall frame that houses the pocket door when it’s open. In the master bedroom they do a sloppy job of aligning the unit with the 2×4 stud wall. Instead of the door frame and integrated wall section being directly in line with the stud wall, they veer out at a noticeable angle. A deficiency, which if left uncorrected will cause problems when it comes time to install drywall, and will cause the door to slide back and forth at a funny angle to the bedroom wall.

I have other deficiencies to discuss with Nick as well, and I phone him and ask him to meet me at the house. Together, we examine the misaligned pocket door frame and he agrees it’s misaligned and needs to be made straight. Luckily, the wall section of the unit hasn’t yet been glued to the slab, so correcting the problem should be easy. Nick assures me he’ll have Dylan and the other carpenter properly align the door frame.

When I inspect the results the next day I’m stunned. The unit is still misaligned, but now glued to the floor. Charles Bukowski: “…it’s not the large things that / send a man to the / madhouse…./ but a shoelace that snaps…” I’m in a cold fury. At the same time, in another, still rational part of my brain, I assemble these possible explanations for this latest piece of idiocy: a) Nick forgot to tell Dylan and the other carpenter to properly align the door frame, b) Nick lied to me and had no intention of telling them because he didn’t consider the misaligned frame a significant problem, c) Nick did tell them, and they forgot, or d) Nick told them and they ignored him, because they don’t respect him. The actual explanation for the misaligned door frame, and for the two dozen other things that have gone wrong, ultimately doesn’t matter. Only the results matter. And the results are shit.

This is the moment at which I fully accept what’s been a growing realization. The problem isn’t Nick’s overextended, second-rate workers. The problem is Nick’s third-rate management of his second-rate workers. The following morning I make the call and discontinue our relationship — or so I thought.

Hiatus

March and April 2008. We’ve gotten rid of Nick, but we still have no furnace, no laundry, and an uninsulated, gutted basement generating no revenue. We must keep moving forward, but we aren’t sure whether to revert to our initial approach of managing the renovation ourselves, or to go looking for a new general contractor. In the immediate aftermath of the Nick experience we don’t have much appetite to begin a search for a new general contractor, so although we know we’ll probably have to go that route eventually, for a while we try to move the renovation forward ourselves.

Our first attempt at making some progress is to contact the electrician and the plumbing company who performed the initial rough-in work in the basement. This work seems fine, and the electrical inspector has told us the electrician is reliable and does good work. My wife leaves a voicemail for the electrician explaining that we’ve parted company with Nick, but we’d like to keep him working on the job. The electrician doesn’t return the call. Months later, the electrical inspector tells us the electrician was conflicted about what to do, and felt bad, but ultimately came down on the side of Nick, because that was where future work was likely to be.

The owner of the plumbing company does return my wife’s call, and tells her he’s willing to complete our job, as long as it can be done on the quiet. He doesn’t want Nick finding out, which could jeopardize his business relationship. He says he’ll get back to us with some dates, but we never hear from him, and decide not to pursue it. It’s becoming obvious that we need to make a clean break from anyone associated with Nick.

We contact our builder friend, who’s working on the high-end renovation in West Vancouver, and ask his advice. He comes to the house to assess the situation. He considers the framing done by Dylan and the other carpenter “rookie stuff,” and the splitting out of the joist notches a farce. He and his crews have always prided themselves on the quality of their framing, but he admits they sometimes wonder why they go to the extra effort when so many builders get away with slapping together the frame of a house, and then quickly hiding all the deficiencies behind drywall. Our friend offers to give us the contact information for the framer and the drywaller on his current job, both of whom he considers excellent. As he’s leaving he looks up at the beam spanning the opening in the central supporting wall and notices something. He grabs a nearby stepladder and climbs up so he can eyeball down the length of the beam. “This beam’s sagging,” he tells us. I climb up and clearly see the slight sag. The beam has been in place only four months, so with time it could very well sag a lot more. Our friend asks if this is the size of beam specified by the structural engineer. I tell him that originally it wasn’t, a taller, narrower beam was specified, but Nick wanted space above the beam to run plumbing and electrical back and forth, so he negotiated a different shape with TK — less tall, but wider to compensate.

“Beams don’t work like that,” our friend tells us. “They get a disproportionate amount of their strength from their height, not their width. Did the structural engineer revise his drawings and sign off on it?”

“No,” I tell him. “My understanding is it was all done over the phone.” And TK’s English is hard to understand over the phone, and it’s quite possible that Nick didn’t communicate his intentions very well.

“Then this beam isn’t to spec. It’s going to have to be replaced with a proper sized beam.”

It’s starting

During this period, there are some other developments. At the end of March, I resign from the company where I’ve been working for the past three years to take a similar job with a different company. A co-worker at the first company made an identical move a year previous, and encourages me to join him at the new place. I’m initially reluctant, feeling some loyalty to the first company, but I’m worried about the company’s long-term viability. I’ve come to feel the company is badly mismanaged, and future bankruptcy is possible. The company has already been shrinking to survive, laying off a quarter of the staff the previous October — a stressful, unnerving event for a small, tightly knit company with a number of longstanding employees. I feel my position is relatively safe, however if the company does go belly up in a year’s time, I don’t want to be job hunting in the middle of a recession. I’ve been following the US economic news to some extent, not closely, but paying enough attention to know that things are not good south of the border. In fact, the US, in the first quarter of 2008, officially slips into recession. As I recall, there’s soothing talk around this time from some Canadian economists and politicians who would have us believe that a mysterious economic delinkage has occurred between Canada and the United States. The US economy might crash and burn, but somehow Canada will avoid being dragged down this time, perhaps by selling resources to the Chinese. This line of reasoning sounds like bunk to me. I discuss with my wife the various factors at play and she encourages me to make the strategic move from a shaky, small company, to a medium-sized company with sounder finances. I feel pretty good about my decision to change employers as the global financial crisis accelerates throughout 2008, and it becomes apparent that ‘global’ does include Canada, and that a five-alarm fire at your next door neighbour’s house can make your own living room a little warm.

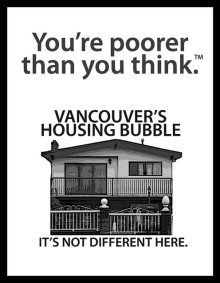

It isn’t only mainstream media news stories about the US and Canadian economy that underpin my sentiments. For at least a year and a half, and perhaps longer, I’ve been soaking up opinions, claims, explanations, statistics, and dark predictions from the Vancouver real estate blogosphere. I don’t remember the exact circumstances, but I probably stumbled on my first Vancouver real estate blog some time in 2006, and it was probably the blog run by VHB, the Vancouver Housing Blogger. What I do know is that VHB and other local bloggers helped me think more critically and analytically about Vancouver real estate and about money. From the time we’d bought the house in September of 2003, I’d been telling myself, in a somewhat vague, uncritical way, that Vancouver house prices couldn’t keep going up forever, and yet every year, in startling fashion, they had continued to go up. Now I’d found an online community that was providing very specific and reasoned arguments why Vancouver real estate couldn’t keep going up forever, and in fact, was very likely to come crashing down. When I wasn’t frantically searching for construction information, my early mornings were no longer spent comparing houses and prices on RealtyLink to our own house. I was now a habitué of the ‘bear blogs’, or the ‘bubble blogs’ — “doom blogs,” as my wife called them. And in April of 2008, while we’re trying to keep our renovation moving ahead, come the first inklings that the doom bloggers’ predictions are starting to come true. There’s a sense that the bloggers smell blood. Through March, April, and May, Vancouver house prices stop rising, but perhaps more importantly, during what should be the prime selling season, year-over-year sales numbers plummet, and the inventory of unsold houses quickly swells, a reliable precursor to falling prices. The April 12th post on the blog Housing Analysis is ominously titled “It’s Starting.” The April 29th post is titled “Vancouver’s Next — Watch Out!” At the very moment that we’re drawing down significant amounts from a line of credit based on the unrealized equity in our house, there’s a good chance house prices could tank and that equity shrivel.

Seismic upgrading

Perhaps appropriately, the one portion of the renovation I do manage to move forward during March and April is the seismic upgrading — making the house more resistant to the forces of an actual earthquake, while pondering the possible results of a financial one. With the wood frame and the concrete foundation of the house fully exposed on the lower level, I take advantage of the opportunity to bolt the frame to the foundation, and install steel structural connectors in other locations, without having to rip off drywall and tear out insulation to do it. I also triple the studs at the corners of the house, in preparation for creating sections of shear wall — half-inch structural plywood nailed to the studs, and the top and bottom plates, of the cripple walls. In certain house designs, cripple walls are the short, exterior walls of the house that run from the top of the concrete foundation walls to the underside of the joists supporting the main floor. In Vancouver, where the mild climate doesn’t necessitate deep basements to protect against frost heave, the typical house of a certain age is basically a box from the main floor up, which sits on stilts or dominos — the short studs of the cripple walls — which themselves sit on shallow foundation walls. This design works well enough when bearing the vertical load of a house subject to gravity, but it’s inherently weak when it encounters the side-to-side shaking or shearing forces of an earthquake. Cripple wall failure is the most common residential structural failure in an earthquake. The ‘box’ portion of the house moves laterally as a single unit, collapsing the stilt-like studs of the cripple wall beneath it, and slumping to the ground. Not a pleasant thing to have happen to your house, and especially not a pleasant thing if there are tenants living in the space beneath the ‘box’ portion of the house — which will be the case with our suite, and is the case with the vast majority of basement suites in Vancouver. Attaching plywood to the cripple walls strengthens them enormously, allowing them to resist shearing forces much more effectively.

Seismic upgrading was another aspect of the renovation that Nick and I disagreed about. He maintained that unless you could establish a continuous load path — reinforcing every key connection point between framing members from the foundation to the roof — there was no point doing anything, because the earthquake forces would act upon the weakest link. He did agree with bolting the frame to the foundation. It’s true that establishing a continuous load path is the ideal situation, but Residential Guide to Earthquake Resistance, and various other sources I find on the Web, explicitly state that if homeowners do nothing else, bolting the frame to the foundation, and reinforcing cripple walls, can save a house, and its occupants.

Drilling hole for anchor bolt

Drilling hole for anchor bolt

The return of Nick

How does this happen? I don’t know… but it does.

Although we’ve broken off the contract, we have to settle on a final amount of money that Nick claims is owed in excess of the original $20,000 deposit. There are also some loose ends that need to be wrapped up. There are tools and supplies to pick up, and a portable toilet that has to be removed from the site. Not surprisingly, Nick doesn’t attend to these things particularly promptly. I phone him on several occasions to prod him into action. During one of these calls, I mention that the beam in the central supporting wall has sagged and will need to be replaced.

At some point, Nick phones us and asks for a meeting. He tells us that he wants to make things right, to deal with all the deficiencies, including the beam, at no cost to us. This last part is a bit of a laugher, given that we’ve already paid to have the work done properly. In fact, Nick’s own contract states that all work will be done in accordance with good quality standards, and in compliance with the applicable building code and related inspections, and “other authorities” (i.e., TK). You can’t charge clients to fix your own mistakes.

We agree to the meeting, but nothing more. Nick pitches his new line: he’s going to put his top guys on our job (thereby implying that we didn’t have his top guys before — in fact, as we’ll later find out, he’s fired Dylan). He’ll pay for a new beam and its installation, the tripling of the joists that TK has specified to account for the split joists, and the materials and labour required to fix a number of other more minor deficiencies. After the work is complete, we can decide if we want to continue with the contract or settle up and call an end. We tell Nick we’ll give him an answer in the morning.

After Nick leaves, my wife and I discuss his offer. We agree that it’s unlikely the leopard can so thoroughly change his spots, but there doesn’t appear to be much downside. I phone Nick the next day and tell him he can come back under the terms discussed once we get a revised beam specification from TK. I also tell him that every aspect of the operation — his “top guys,” the results of their work, and Nick’s management of the work — will be under a microscope.

Given his performance to date, Nick’s sudden eagerness to make things right is a bit puzzling. Perhaps he’s worried about his professional reputation. In hindsight, I wonder if the rapidly deteriorating economy in the spring of 2008, and in particular the rapidly deteriorating circumstances for real estate and construction, was causing his business to dry up, and that he saw our job as salvageable.

Shit 2

I ask TK for a revision of the structural engineering drawings, one with a new beam specification and detailed seismic upgrading information. We can’t simply revert to the original beam specification, I discover, because changes we made to the suite layout along the way mean the opening in the central supporting wall is two feet wider than indicated on the original drawings — something Nick either failed to take into account, or failed to communicate effectively to TK, and another likely reason that the installed beam sagged. We want to keep the wider opening, so we need a revised beam specification.

TK is very slow in getting to the revision. A couple of weeks go by, and we’re still waiting for what is probably 15 minutes of work for TK, and an hour for one of his assistants to modify and reprint the drawings. I begin hounding TK daily, and I suspect that at times he’s screening out my calls. I start phoning from different locations around my work place, and whenever I phone from a new number, he answers. My wife eventually loses all patience, and in a rage flies down to TK’s office, blowing in like a tornado and terrorizing TK’s dopey staff. Tellingly, they’re able to produce the revised drawings in about ten minutes. A cowed TK slinks into his office during this showdown. No questions, during this second meeting with my wife, about why we haven’t started a family.

(Revised drawings: $900)

I phone Nick with the details of the new beam, and around the end of May, his top guys start the work. Within a couple of days, the new beam is in place and the joists are tripled and attached to the side of the beam with joist hangers. The results seem better. However, when TK comes to inspect, he immediately sees something he doesn’t like. On the third joist added to each joist pair, the two cuts forming the notch extend slightly past each other where they meet — the result of cutting the notches entirely with a circular saw, rather than cutting them mostly with a circular saw and then finishing the cuts with the straight blade of a handsaw or reciprocating saw. The slight overcutting doesn’t seem that critical to me, but TK announces that before he’s willing to sign off on the work, four-foot-long plywood gussets — plywood cut to the shape of the notched end of the joists — must be attached to either side of each triple joist as an additional strengthening measure. He’ll need to do another drawing. I don’t know whether this latest pronouncement is a scam to further inflate his fees, or a legitimate requirement from a structural standpoint. Either way, we don’t have much choice but to comply if we want him to sign off.

After TK leaves, I discover something of my own that I don’t like. The joist hangers are triple-width, 2×8 joist hangers cut down in size to approximate a triple 2×6 hanger, necessary to fit the notched end of the joists. In preparation for doing more seismic upgrading work, I’ve been reading the literature from the structural connector company, and they repeatedly warn against making any manual alteration of their connectors. Each type of connector is specifically engineered for its particular purpose, with nail holes positioned in precise spots. Chopping bits off connectors, especially bits that contain nail holes, as is the case with the altered 2×8 hangers, can significantly reduce their load-bearing capacity, and is definitely bad practice.

I tell Nick about TK’s latest pronouncement. He thinks the gussets are complete overkill, but agrees there isn’t much choice but to comply with TK’s wishes. I also bring up the issue of the cut-down joist hangers and he agrees to swap them for properly sized triple 2×6 hangers.

TK produces the required drawing much more quickly this time — perhaps wanting to avoid any further encounters with my wife — and includes it in the price for the just-completed site inspection, which is covered under Nick’s contract. I phone Nick and tell him that I have the drawing and will leave a copy on the work table in the suite, which I do as soon as I get off the phone. I also remind Nick about swapping in the correctly sized joist hangers. “Don’t worry, I’ll take care of it,” he responds.

The following morning I discover another potential problem. Nick’s guys have used 1-1/2 inch long hanger nails in the ‘shear nailing’ locations on the joist hangers. 1-1/2 inch hanger nails — nails that are thicker and stronger for their given length than regular nails — are the correct fasteners to use for the nails that go straight into the beam (step 4 in the joist hanger diagram above). However, I’m almost certain that I’ve read longer nails are required for the shear nailing locations, where nails are driven in diagonally at a 45 degree angle, thus requiring greater length to properly penetrate the beam (steps 5 and 6 in the diagram). When trimming the joist ends to make room for the flush beam, Dylan had done a sloppy job, overcutting some of the joist ends by as much as an inch. There is very little wood inside the hangers on these joists. The combination of the short nail and the lack of wood allows me to reach up to a shear nailing location on one of the joists, and with almost no effort pull a hanger nail free. The nail isn’t biting into anything. It’s just there for show. At work later that day, I go to the manufacturer’s web site and confirm what I thought I’d previously read. In numerous locations in their literature they expressly state that hanger nails must not be used for shear nailing. Shear nails must be at least 3-1/2 inches long.

Sloppy trimming of joist ends

Sloppy trimming of joist ends

Volcano

I get home and go downstairs to check the progress. I have another one of those moments when I’m stunned by what I see. The plywood gussets have all been cut incorrectly. Instead of the sideways L-shape required to match the notched end of the joists, they’re straight strips. Several of them have been installed, with nails spaced every two inches as TK required — a crapload of nails over a four foot length — but doing absolutely zero from a structural standpoint, because they run above the notch instead of wrapping around it. The uninstalled gussets — now useless pieces of wood — are stacked on the work table, about six inches away from TK’s drawing.

The remainder of the joist hangers have also been installed — not the properly sized triple 2×6 hangers that Nick promised he’d take care of, but more triple 2×8 hangers with bits cut off.

I tear out of the basement and pound up the deck stairs to the phone above. For a fleeting moment, cresting the top step and crossing the deck, I have a strange, floating sensation, definitely out of control, but more, an almost out-of-body sensation, the sense that I’m not quite sure what’s going to happen next, that anything could happen. Thinking back, it’s perhaps not unreasonable to describe the momentary impulse as homicidal. If someone had been there to capture the instant with a camera, what would my face have looked like?

I get Nick on the phone. Six months of deficiency after deficiency, of ignorance of the building code, of ignorance of construction techniques in general, of garbage work, of repeatedly absent workers, of being manipulated, of being lied to, of worthless promises, of non-existent oversight, of having our hopes raised only to have them dashed, of moronic decisions, of babysitting incompetence, six months of rage, come pouring out like a volcano. Inside my chest a huge pressure accompanies the river of profanity I bellow down the phone. “DO YOU WANNA BE FUCKING FIRED?” Nick tries to calm me down, says he’ll come over right away. “YOU’RE GODDAMN FUCKING RIGHT YOU’LL GET OVER HERE RIGHT AWAY!” I rage on for about a minute, then slam down the phone as if trying to smash it right through the coffee table.

On the other side of the French door, in the kitchen, I see my wife’s alarmed face. Later, she tells me she’s never seen me that angry. Ever. Even though the doors and windows were closed, she tells me that the whole block heard.

I go into the backyard and take a number of deep, even breaths, feel the mild evening air flowing in and out of my lungs, slowly lowering my blood pressure. I go into the basement to await Nick’s arrival. By the time Nick shows up, about ten minutes later, I’m mostly back to normal. Through the front window I watch as he, and another guy, get out of Nick’s car. I don’t recognize the other guy, but I assume it’s one of his workers. Although it seems strange that one of his workers would still be around at this hour of the evening. As the two of them come up the walkway toward the house I can see the worker is really burly, with the body shape you get from thousands of hours spent pumping iron in a gym. I have to work hard to keep myself from laughing when I realize Nick, a deathly serious look on his face, has brought along a bodyguard.

Everything is weirdly cordial after the eruption. I shake hands when introduced to Nick’s worker. Nick makes some excuse for the screw-up with the gussets and the joist hangers and says they’ll be fixed. I then tell him about the problem with the short shear nails, and pull a couple free to demonstrate.

“Those are hanger nails,” he protests.

“Yeah, I know. But the company’s literature explicitly states you don’t use hanger nails in the diagonal nailing locations. They specify a 3-1/2 inch nail.”

Nick isn’t convinced, but tells me he’ll phone the company in the morning to verify what sort of nail should be used. Then he and his worker leave.

Shoelace 2

…it’s not the large things that send a man to the madhouse….

Nick’s mild protestation that “those are hanger nails” is what finally does him in. He’s completely sincere in that particular statement because at that moment that’s what he absolutely believes. And there are probably houses around Vancouver with the wrong sized shear nails in their joist hangers because Nick was the general contractor. Will those houses suffer structural failure? Probably not. But it doesn’t matter. I’ve finally realized that it makes absolutely no sense to be paying someone thousands of dollars to provide a service in which you have absolutely no faith. To feel that you have to double- and triple-check every decision you’re paying someone to make. To live with the constant anxiety that every additional piece of work someone does on your house could be damaging it even further.

In the morning Nick phones and tells me he’s spoken to the company and that I’m right about the shear nails. “I know,” I say. And then I tell him it’s over.

What happens the rest of the way

With the final departure of Nick, the high drama ends. Lawyers get involved, and on the advice of our lawyer, we eventually settle with Nick for an additional $5000.

(Nick’s settlement: $5000)

I keep plugging away on the seismic upgrading, and we hire a tile company to install a waterproof membrane and slate tile on the front stairs. The stairs end up looking really good, although ironically, appearance wasn’t the reason we undertook the work.

(Seismic upgrading, tool rentals and materials: $1360)

(Waterproof membrane and tiling: $4150)

Toward the end of summer, we have a bit of luck. While talking with a co-worker, my wife’s sister relates our renovation saga. The co-worker suggests getting in touch with her husband, a general contractor and custom home builder. She says her husband has spent an entire career in the industry, and is very focused on quality, and detail, to the extent that he sometimes drives his tradespeople crazy. This sounds worth following up. I check out the husband’s company web site, and I’m impressed, although I feel he may be out of our league.

Over the next month we have several meetings with Ray, and end up hiring him mid-September, 2008. His company is busy, finishing up a large project, and he won’t have a crew available until some time in the new year. But he’s willing to come in himself before then and do the work necessary to move forward with the installation of the new furnace and heating duct system, and to bring in his plumber to run the lines for the upstairs laundry. I assist with swapping in properly sized joist hangers, and with removing the incorrectly sized plywood gussets and reinstalling proper ones. One morning in early October my wife and I are standing with Ray in the basement when one of the heating technicians fires up the new furnace for the first time. The warmth wafting down from the newly installed heating registers overhead is intoxicating. Eighteen months without a furnace, and almost a year of humping bags of dirty clothes to the laundromat, have come to an end.

(New furnace and heating duct system: $15,000)

From this point forward, the renovation runs pretty smoothly. Because of last-minute add-ons to the big job they’re wrapping up, the crew doesn’t become available until the middle of March, 2009. I use the intervening time to complete all the seismic upgrading work in the suite, with the exception of attaching the plywood panels to the cripple walls, which the crew will do. In order to install pieces of seismic hardware known as a holddowns at the inside corners of the house, I rent a large rotary hammer drill to drill one-inch diameter holes fourteen inches deep in the concrete foundation walls. This job is sort of fun, but a bit stressful. After consulting with Ray, I also rip out those portions of the framing done by Dylan that are substandard — about two-thirds of it. Once the crew does start, progress is quick and the results are very good. Ray proves to be everything his wife, and his references, described: detail oriented, knowledgeable, responsible, and calm. In a word, professional. We discuss in advance various options for particular aspects of the renovation, agree on an approach, and then that’s what happens. Workers arrive at 8:00 am, work all day, and when I inspect the results at the end of the day, there’s significant progress and I don’t find anything remiss. And by this point I’ve developed a pretty good eye. I eventually stop checking if things are plumb, level, and square, because they always are.

The crew works steadily on our job for about ten weeks, and then more sporadically throughout the summer as they wait for my wife and I to do the insulation, including installing insulation in the ceiling for better soundproofing, and then later to paint the entire suite — portions of the renovation we do ourselves to try to save some money. In retrospect, the $1500 we save doing the painting, which takes five or six prime summer weekends, is a poor tradeoff.

Here’s a list of what the renovation includes, in the order that the work is done:

• Removal of the old stucco siding and the old soffit under the eaves

• Installation of new windows for the entire house (purchased from a company recommended by Ray, rather than the initial company we’d been dealing with)

• Installation of a rainscreen

• New soffit all around

• Demolition of the rear deck superstructure, replacement of the old decking

• Re-siding of the entire house with cedar

• Suite framing, including plywood shear walls

• Demolition of the upstairs bathroom

• Replumbing of the entire house

• Rewiring of the bottom half of the house, and installation of separate electrical panels downstairs and upstairs

• Installation of new exterior doors for the entire house

• Lighting throughout the suite

• Insulating and installing vapour barrier in the suite and upstairs bathroom

• Drywalling the suite and upstairs bathroom

• Tile flooring in the suite, and tile flooring and shower surrounds in both bathrooms

• Cabinet, counter, and cupboard installation in the suite kitchen and both bathrooms

• Interior doors in the suite

• Interior window and door trim for the entire house

• Exterior concrete work

• Suite appliances

• New deck railings and stairs

• Interior painting of the suite and upstairs bathroom

• Exterior painting of the entire house

• Hardwood flooring in the suite

• Baseboards in the suite

• Closet shelving and rods in the suite

• Attic insulation increased to R50

Re-siding the house wasn’t part of our original plan. But once we gutted the basement we discovered that the building envelope — basically a couple of layers of building paper under the stucco — was beginning to fail and in places water was seeping through the shiplap sheathing boards. A new bathroom upstairs wasn’t part of the plan either, but we decide to include it once Ray explains that it’s much more cost effective, and less disruptive, to replumb both the downstairs and the upstairs bathrooms at the same time, rather than return to do the upstairs one at a later date. Besides which, both my wife and I really hate our old upstairs bathroom.

By our estimation, we rebuild about 50% of the house over the course of the entire renovation. We decide to leave the interior renovation of the top half of the house, with the exception of the bathroom and the windows and doors, until later. We could have moved into the rental suite for a period of time, and had Ray and his crew renovate the top half as well, but we’re physically and psychologically exhausted, and we’ve maxed out our line of credit. We need a break, and we need to restart the stream of rental income.

At the beginning of September, 2009, tenants move into the new suite, three years and one month after the previous tenants moved out of the old suite.

The final reckoning — sort of

After Ray takes over the renovation, the drama that does exist involves money, and the players are my wife, me, and our line of credit.

Ray and his crew are not cheap. The contract with Ray is straightforward. Rather than a set price, he charges the hourly rate that he pays his own workers, the invoice amount submitted by the subtrades such as the plumber and the electrician, the contractor price for materials (typically somewhat cheaper, and sometimes significantly cheaper, than the retail price), and then adds 15% of everything for his fee. This arrangement is spelled out in advance, written down on a single sheet of paper, and Ray never deviates from it for the entire duration of the renovation.

Ray’s two senior workers on the job, skilled and experienced guys, one of whom used to run his own construction company, are $65 an hour each. A more junior worker is $37.50 an hour, and a labourer $20 an hour. The senior workers also negotiate an hour of paid travel time a day, each, because they live in distant suburbs and could easily find work much closer to home. We’re not that thrilled about the travel time, and Ray understands and gives us a choice of using different workers who wouldn’t be paid travel time, but he feels that the two workers he’s recommending would have the best mix of skills for our job. So we agree. Although it’s September 2008, and the global financial crisis is in full throttle, with shocking news coming out of the US almost daily, it seems the market in Vancouver, at least for builders with good reputations, still bears a lot.

Earlier in the year, we meet and become friends with a neighbouring couple who live in their mostly renovated 1920s builder’s special about a block away. They’ve done a great job on their place, working at it on and off for the past decade, often by themselves, but during one phase, that included raising the house and pouring a new foundation, hiring a construction company. They tell us that when a construction crew is going gangbusters on your place, to expect invoices equaling about $10,000 a week. We’re shocked, but that turns out to be exactly what Ray and his crew cost us. During the initial, intense, ten-week period of work, Ray presents an invoice every two weeks, and the average amount is almost exactly $20,000. To begin with, I’m secretly horrified. I can’t believe the size of the cheques we’re writing against our home equity line of credit. I’ve never seen or written cheques this large, with this frequency, in my life. When we renewed our mortgage in October 2006, we had an outstanding balance of $193,000, and a home equity plan that allows us to borrow up to $375,000, including the mortgage balance. So initially we have up to $182,000 available to borrow for the renovation, which in 2006 seemed like a huge sum. Now, in 2008 and 2009, I’m worried it won’t be enough. And if it hadn’t been for our aggressive lump sum payments against the mortgage and the renovation costs throughout the 2006 to 2009 period, it wouldn’t have been. In fact, toward the end of the project, we had to use a smaller, personal line of credit to pay three of Ray’s invoices. By 2009, the bank probably would have given us an increased limit on our home equity line of credit, but that wasn’t something we were interested in, and the interest rates on the two lines of credit were comparable.

By the end of 2008 I’m worried enough about the economic crisis and the ultimate effect it may have on Vancouver house prices, which at this point have been crashing for six months, and credit availability based on home equity, that I seriously consider calling off the renovation, or postponing it indefinitely. We have heat, we have a laundry. Without too much additional expense and effort we could insulate the basement ourselves, and bunker down to weather the economic storm, focusing strictly on debt reduction. We wouldn’t have a rental suite generating income, just an unfinished basement beneath us, but we also wouldn’t be racking up tens of thousands of dollars of additional debt. I float the idea of putting the reno on hold with my wife. She understands the increased risk we’re now facing, but doesn’t want to lose Ray. We’ve been lucky to find him, and have already spent almost four months waiting for his crew to become available, not to mention the previous two years of grief, so letting him go now, without having the benefit of his services, would be painful.