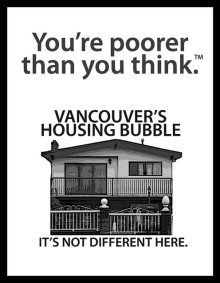

“Steven Patterson and his family moved to Vancouver from Cambridge, Ont., in mid-2008, just as the financial crisis hit. After years of scrimping and saving to pay off their first mortgage, they had earned a tidy profit when they sold the Cambridge house and put the proceeds into GICs, where the money would be safe and easily accessible should they decide to buy another home in B.C. Three years later, Patterson, a 42-year-old IT manager, is still sitting on the sidelines, renting, while real estate prices march ever upward in a city where a three-bedroom bungalow covered in warped siding can fetch $1 million.

That might seem like a prudent move in an uncertain economy, but Patterson says his cautious approach has come at a steep price: all his money is steadily being eaten away by inflation, which the meagre interest income from his GICs can’t cover — particularly after the taxman takes a cut. Meanwhile, several of Patterson’s friends have taken advantage of those same low interest rates, loaded up on debt, and bought into Vancouver’s frothy housing market in recent years. And they have enjoyed a windfall—at least on paper—as the value of their homes continues to climb. As for Patterson, “I’m only a few thousand dollars ahead—minus inflation,” he says, clearly frustrated. “So actually, I’m way behind, and I don’t have a house.”

Welcome to the world of ultra-low interest rates, where profligacy is richly rewarded and saving is, well, for suckers. Those who’ve opted to be austere with their personal finances have found themselves on the losing end as governments and central bankers have worked to get people to borrow and spend in the wake of the global recession. While emergency interest rate cuts were to be expected after the financial crisis seized up lending markets, it’s been nearly four years since central banks started slashing rates to the lowest levels in history.

—

As a result, those saving money have seen almost nothing in the way of returns for a painfully long time. In fact, after accounting for inflation, anyone who dares to be prudent risks seeing the value of their money decline. If one were to put $10,000 into a five-year GIC at two per cent this year, and assume headline inflation goes no higher than the current rate of 2.7 per cent, the future value of that investment in 2016 will have shrunk to around $9,670.

For seniors and others living on fixed incomes in particular, low rates threaten to wipe out their savings. Yet it’s also depressing for those in the second half of their careers who don’t have an appetite for risk but feel they now have no other choice. “People in their 50s are worried about what they’re going to retire on,” says Susan Eng, vice-president of advocacy at CARP, which works on behalf of aging Canadians. Between the carnage in stock markets and the collapse of interest rates, “there’s a huge amount of anxiety. You’re asking for a lot of trouble with this situation.”

—

Some will argue people like Patterson are simply bitter because they didn’t buy into Vancouver’s soaring housing market. And yes, those who take risks should enjoy the potential for greater rewards. That principle is at the heart of capitalism. Only, in the current environment where central banks have pushed down interest rates to abnormally low levels, and government policies encourage consumption over thrift, the dynamics of risk and reward have been severely distorted.

This isn’t how it’s supposed to work. From the moment children are given their first penny, it’s driven into us that saving is a virtue and the path to financial security starts with that ceramic piggy bank on the dresser. Only now, with policy-makers in a desperate race to reignite economic growth, all that has been turned on its head. Yes, Bank of Canada governor Mark Carney and Finance Minister Jim Flaherty have repeatedly warned Canadians not to take on too much debt, but their policies, and those of their colleagues in countries like the United States and Great Britain, have had the opposite effect, encouraging people to buy homes, cars, flat-screen TVs or take a plunge into volatile stock markets—anything, that is, but save.

—

“We’ve got ourselves into a position where debt and spending seem to be highly valued, but saving, which is prudent and helps people plan for their futures, seems to be almost looked down upon,” says Simon Rose, who works with Save Our Savers, a British organization that’s taken up the fight for downtrodden penny counters. “It’s unfair that the problems of the economy should be disproportionately shouldered by savers rather than those with a tendency to borrow too much and get into trouble.” No one is saying Canadians should abandon thrift and go on a wild spree of gluttonous consumption. Indeed, Ottawa has set up tax-free savings accounts to encourage people to save. But the competing priority of spurring economic activity means the interests of savers have taken a back seat and made it that much harder to act responsibly. What’s more, while central bankers have undone basic thinking about saving in the name of juicing the economy, a growing chorus of critics claim that strategy has not only failed to turn things around, but the dogged pursuit of low rates might be weakening the recovery

—

Sometimes Lee Tunstall wonders why she bothers saving at all. A child of parents who grew up during the Second World War and instilled in her the importance of living within her means, Tunstall, a consultant in Calgary, has rented the same apartment for 17 years and dutifully contributes to her conservatively managed RSP account. Yet all around her, friends have piled on huge mortgages and run up towering lines of credit debts in the past few years to buy homes and new Bimmers for the driveway. “If you are a saver you’re absolutely losing money to inflation, and if you go into the markets you’re losing money there too, so why bother?” she says. “Sometimes I think, ‘Why don’t I just join the herd and do what everybody else is doing, buy the toys and live it up like everybody else?’ ”

Tunstall would have plenty of company were she to give up her frugal ways. Gone are the days when Canada was a nation of savers. In 1980, the personal saving rate peaked at above 20 per cent and was still around 13 per cent in 1995. Today it stands at just 4.1 per cent. At the same time, over the last decade Canadians have increasingly relied on debt to maintain their lifestyles. The average household now owes $151 for every $100 of disposable income, a higher level than even American households reached in 2007 as the air rushed out of the U.S. housing bubble. This week, Moody’s, the credit-rating agency, said it is increasingly uneasy with the consumer debt mountain rising in Canada. “We are concerned that Canadians are relying on low interest rates to support high debt levels,” the agency said in a statement.

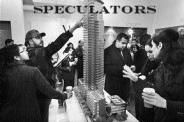

Much of that growth in debt has taken place since 2007, when the Bank of Canada cut its overnight rate from 4.5 per cent to a low of 0.25 per cent in 2009. The dramatic cuts, along with stimulus programs targeted at the real estate sector, revived house prices, which had begun to tumble. As of June, the Teranet-National Bank House Price index has nearly doubled over the last decade, while in markets like Vancouver, prices have soared a whopping 140 per cent. That shouldn’t have been a surprise; reckless behaviour gets a boost when government and central bank policies punish individuals for not taking part. But while the cuts were a boon to mortgage borrowers, they’ve sideswiped the saving crowd.

One way to measure the impact is to look at how much interest income is being lost as a result of low rates. Stephen Johnston, a Calgary money manager, estimates that with roughly $1.2 trillion on deposit at the banks and rates roughly three percentage points below their historical average, savers are losing out on $30 billion to $40 billion every year in interest income. He argues this amounts to a massive subsidy for the country’s banks, since the rate depositors are paid to part with their money is far less than what the banks can earn lending that money out to other people as mortgages. “Deposit rates now cost the banks nothing, but that’s not free,” he says. “Someone else is paying the price, and it’s little old ladies and people on fixed incomes who can least afford it.”

—

With Canada’s overnight rate at an almost-princely one per cent compared to the U.S., savers have at least had that going for them. Unfortunately, Canada’s economy shrank by 0.4 per cent in the second quarter, reviving calls for more rate cuts. At the very least, Carney now says the need for a rate hike has been “diminished.”

—

For its part, the Bank of Canada is in a difficult spot. If it leaves rates low indefinitely, there’s the very real risk more Canadians will decide saving is a suckers’ game and start to pile on debt. Yet when the bank eventually does raise rates, which it must, someday, over-indebted households could spark a fresh crisis. “Previous generations used to buy a house that was twice their household income, but now families are spending 10 to 12 times what they earn,” says David Trahair, a financial author whose new book, Crushing Debt: Why Canadians Should Drop Everything and Pay Off Debt, is due out in November. “The central banks are in a bind because they can’t increase interest rates or it will be extremely punitive to these people with mountains of variable rate debt.”

Whatever happens, Ritchie Hok, an actuary living in Ottawa, is convinced savers will ultimately wind up paying the price for others’ imprudence. At the peak of the U.S. housing bubble, Hok lived in Minneapolis and saw the excesses first-hand. While there he resisted those who urged him to get into the market; a wise move given prices are down 40 per cent there. Now that he’s in Ottawa, though, he’s hearing all the same arguments for why he should take advantage of low rates and buy a house before prices rise even further. He’s convinced Canada’s housing market is a bubble that will eventually burst, and when it does, policy-makers will rush to people’s rescue. “My fear is that most people in Canada are now debtors and not savers, and so governments will enact policies to help them because they make up most of the population,” he says. “Savers may get screwed on the way down, too.”

If Hok is right, the frugal few could be in for even more pain ahead. Why is it again that it pays to save?

– liberally excerpted from ‘What’s the use of saving money?’, Jason Kirby and Chris Sorensen, Macleans, September 27, 2011

As street-smart youngsters may say: “Word!”. -ed.

If you’re worried about governments bailing out risk takers, consider first the magnitude of the task. Say the average home is $300k and there are 10mm homes. If prices are 20% above the fair value as measured by price-rent that’s $60k * 10mm or $600 billion in bailout monies, or 50% of GDP.

Sure the government will be forced to “bail out” bad debt via CMHC obligations and add a few billion to a distress relief fund but the cold truth is that most of the burden will lie on the backs of debtors. Protestantism requires it.

It’s not the actual bailing out that bothers one (too big a task, granted); it’s the attempts that will be exhausting.

And the fact that we’re all on the hook, regardless of whether we benefitted. Moral hazard.

OK good point. Read the narratives in the US and few are pleased prices are falling, at least publicly. My bet it won’t feel so much like euphoria but will feel like humility when buying at significant discounts.

Not buying but renting is a hedge for many, so the losses are reduced but not eliminated.

Would it be preferable for the B. of C. to raise rates now? Better an easing-off of the addiction than the short-sharp-shock that will inevitably occur at some point down this road. Better that than the scenario of widespread economic and social damage that will last for decades. No more jobs, no more money for education or health care or roads or parks or municipal works. Our neighbor to the south continues to writhe in major pain. In this regards, there’s no short-sharp-shock but something far more chronic.

And while one positive result may be the significant discounting of house prices, the actual ability to purchase those discounted homes may prove impossible for most. (U.S. banks have made lending extremely difficult, unless one is armed with truckloads of cash).

“Would it be preferable for the B. of C. to raise rates now?”

Canada and the banks really are in a bind. The US is heading into a double-dip and Canada needs to play defense in order not to be pulled down.

this is the age old argument of renting vs owning. You can never keep pace with the rising value of housing by saving money. This has pretty much always been the case over the long run. The fact that this current run up has been steeper than most has accentuated this renters classic error in judgement.

A modest 5% yearly inflation in a Vancouver detached property means a renter would need to save more than 45K/year to keep pace with the price increase. Little wonder Steven Patterson is still renting and waiting, and waiting, and…

“You can never keep pace with the rising value of housing by saving money”

But consider this: once the bubble ends, as has pretty much always been the case over the long run, you can never keep pace with the falling value of housing by saving money. Meanwhile, your debt remains.

I know several people underwater who wished they had rented during the height.

timing is critical.

Actually, this premise has been incorrect for the better part of a century: “You can never keep pace with the rising value of housing by saving money.”

Houses usually maintain wealth but do not grow it, as per Shiller’s research. Which only makes sense – as an investment, they produce rental value minus upkeep and other carrying costs like mortgage – whereas other investments can generate wealth. Rents are constrained by what people are able to pay for rents, which are in turn constrained by wages.

Vancouver has enjoyed many booms & busts in RE, and has seen real increase over the past 100 odd years. But given the increase in industry and density, that’s not terribly odd. We were barely a stain on the map 200 years ago. We’re still not a bustling economic centre but we have more of an impact than we did then.

But that *can’t* happen forever, because there really is only so much of any economy or business that can go to capital cost before there’s nothing left. You can’t pay all your income to housing because you have to eat. You can’t have all your economy go to housing because then no one can buy anything. You can’t spend all your start-up money on capital costs because then you don’t have anything left over for input.

It’s sort of obvious that capital CAN’T preform better than other investments, when you think about it, because “a place to be” is only one ingredient in any economic recipe.

Well said, Absinthe.

“If you are a saver you’re absolutely losing money to inflation, and if you go into the markets you’re losing money there too, so why bother?” she says.

untrue. Inflation in Canada has been in check for years now. This renter is not losing pace with inflation, she’s losing pace with her home-owning peers.

Obviously, you haven’t bought groceries for your family in the last 4 years (nor have you probably worked a professional job in your life so you wouldn’t know what downard wage pressure is but this is beside the point).

Real interest rates have been negative for 3 years – even if you believe inflation has been 2% So it appears that you are wrong on this account even if you are right that savers/(renters) have lost pace with housing debtors. Eventually in a zero interest rate policy world, the table will turn and you as a debtor will be losing much more money than the saver/(renter).

core inflation has been below 2% since 2009. So are you complaining about losing 1% on your $400 monthly food bill? I think your beef really should be about losing 5K/month to rising Vancouver property values.

The table may turn for a short time, but you’ll never regain what you’ve lost by renting.

I’m shocked that you can feed your family on $400 per month! – you must be serving dog food at least once a day. I mean, 100$ per month in milk is a reasonable budget if you have a family.

Chaz -> “A modest 5% yearly inflation in a Vancouver detached property…”

—

This is the problem.

In the current environment, 5% p.a. is not “modest”, it’s almost twice the inflation rate, and far, far above low risk investments. You have been conditioned to see 5% p.a. as “modest” by the mania.

Long term, housing prices cannot increase by more than the rate of increase of wages. When the Vancouver market crashes, we will return to that mean.

“In the current environment, 5% p.a. is not “modest””

This is such an easy concept it’s amazing how few understand this.

“5% p.a. is not “modest”, it’s almost twice the inflation rate, and far, far above low risk investments”.

that’s the ticket vreaa, house prices rise faster than inflation so you’ll never be able to keep pace. 5% for Vancouver is historically low – so let’s compare apples with apples.

Boy, you’re confused.

My statement was to show how even 5% p.a., what bulls consider to be “modest”, is unsustainable. And, yes, we do mean for Vancouver.

“house prices rise faster than inflation so you’ll never be able to keep pace. 5% for Vancouver is historically low – so let’s compare apples with apples.”

Um… house price appreciation is based on utility in the long run. 5% average growth in a low-wage-inflation environment is unlikely. This is especially true of condos. If what you state about past performance being an indicator of future appreciation is common knowledge, there is even more reason to be concerned.

Chaz -> “You can never keep pace with the rising value of housing by saving money. This has pretty much always been the case over the long run.”

—

Sure, if your only sample is the Vancouver RE market, over the last 10 years.

If you look almost anywhere else in the world, over almost any other timeframe, saving/investing is better.

Homes are NOT good investments.

But, hey, if you say it enough, it becomes true, right?

Oh and by the way, Chaz, you haven’t answered my question from a few days back:

1. What percentage of your net-worth is in Vancouver/BC RE ?:

(a) 80%

(b) 100%

(c) 400%

(d) 500%

(e) >1000%

Hilarious: eyesthebye believes housing prices will consistently outpace inflation. Who will buy housing, then, and with what money?

The stupidity is astounding. He’s so stupid that I might even feel bad for him when his paper gains evaporate and he discovers what the bursting of a giant credit bubble looks like.

btw, as a reminder, core inflation excludes energy and food which as far as I know is required by almost everyone to live.

Zero interest rate policies have basically lit a fire in commodities and other base materials needed by everyone and have caused disproportionate harm to the lower income people & families. It has also caused havoc with pension funds (less return, higher liabilities), insurance companies, etc which also affect all people who aren’t rich or public servant with access to the “unlimited” government funds for pension benefits.

So while Chaz can gloat right now, pretty soon he will likely end up in the same boat as the saver except he has debt rather than savings.

The result of the low interest rate is two forms of slavery for the many. One form is to be a renter, slave to the landlord as the price of rent will typically take the biggest portion of income. The other form is to be a homeowner, slave to the financial institution that lends you the money to buy the property. The additional slavery is the inability to build meaningful assets in the short and medium term to achieve financial independence from landlords, financial institutions and employers without taking on an inordinate level of risk and uncertainty.

This is a world that suits the owners of large amounts of capital perfectly.

Goodbye to a long term, well paid job.

Goodbye to paying off a house in the short or medium term.

Goodbye to a retirement income that is secure and inflation indexed in the private sector, and in the long term, perhaps the public sector.

Lots of competition for “good” jobs, downward pressure on wages, frequent market corrections to keep people on edge, increased levels of child and working poverty. You wonder how long people will continue to sing the praises of economic policies that provide such dream world for corporations and employers and owners of capital and increased conditions of slavery for the many.