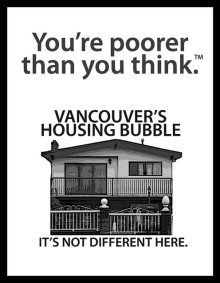

The apparent Vancouver RE ‘boom’ has been based on the spending of imagined wealth. This has involved individual and group self-deceit. As a society, we’ve pretended that local homes are worth twice what they were a handful of years ago, and acted as though they were worth well above twice their value as defined by usefulness. Banks, just as besotted by the game as the rest of us, have allowed some of us to borrow vast amounts of money and commit to ‘buying’ at these fairy-tale levels, and the rest of us have then acted as though these transactions are indicative of true values. Some owners, based on the consequent newly imagined values of their houses, have in turn borrowed money from the banks, and spent it. Sometimes on frivolous toys, but, at least as often, on renovations, or the construction or purchase of new properties. And thus the game has perpetuated itself. The spending both directly and indirectly attributable to this charade is likely ultimately immeasurable. It has been so vast as to allow our economy to seem to weather a devastating recession. But almost none of the imagined wealth or the consequent spending is the result of actual productive activity. It is all the result of the spending of very large amounts of borrowed money. When the game ends, and when our shared understanding of the value of housing returns to levels closer to the historic norm, the debt accumulated through this process will remain. As Bob Dylan says: “Statues made of matchsticks crumble into one another.”

In his wonderful fifth episode, Froogle Scott shares with us his careful observations of the effects of the boom on the houses in his neighbourhood, and describes the process whereby “increasingly massive war chests of home equity” are used to renovate and construct. He coins the henceforth indispensable term ‘Boom Box’ to describe the utilitarian houses that have been built in Vancouver in recent years. He explores streets, houses, and memories. -vreaa

Part 5: Raise or Raze

Renovation and construction mania

I walk around our neighbourhood taking inventory: renovation, renovation, that house raised and a new foundation poured, that one with a second storey added, and there, a house demolished — razed with a “z” — and a new house built in its place. In the six and a half years that my wife and I have lived in the Grandview area of Vancouver, there have been a startling number of major renovations, and demolitions followed by new construction. Weekday mornings, on my ten-minute walk to the SkyTrain station at Commercial and Broadway, I pass through a two-and-a-half block stretch where one house is being raised, another across the street is demolished and a new house is being built, and around the corner two houses are being totally transformed by the addition of second storeys. It’s difficult to find a block that hasn’t had at least one major renovation or new house built in the last few years, and on a number of blocks there have been multiple projects. A renovation and construction mania has seized the neighbourhood, and it’s still ongoing.

.

An inventory

In February of 2010 I decide to do an inventory. My guidelines are simple. I walk all the blocks in the pocket between major streets where our house is located and count the number of major renovations and new houses that have completed since September of 2003, when we bought our house, or projects that are still ongoing. By major renovation I don’t mean new windows and doors, or a new paint job, or a new porch or new deck — and there are plenty of these more moderate renos in the neighbourhood, which I also count and include in a separate category. I mean houses completely gutted back to the studs, or exteriors completely stripped, or houses raised to allow a new full-height basement or ground level, or houses given a full second storey addition. Renovations that often render the original house unrecognizable. I also include obviously new, or newly renovated houses that probably were completed in the year or two before we bought. In other words, I’m doing a somewhat unscientific, anecdotal inventory of the effects of Vancouver’s eight-year real estate boom on one old, established East Side neighbourhood — a place typified for many years by hundred-year-old character houses, a number of them somewhat dilapidated, smaller, workers’ bungalows like the house that we bought, or Vancouver Specials, an earlier wave of replacement housing stock built from the mid 60s to the mid 80s.

.

The pre-boom neighbourhood

Here are two current photographs showing the housing stock that comprised close to one hundred percent of the neighbourhood pre-2002, the year the boom started. The first shot conveniently captures typical houses from four different eras of Vancouver residential architecture. From left to right: a hundred-year-old character house, a 1970s Vancouver Special, two 1950s stucco bungalows, and a 1920s or 1930s builder’s special, a stripped-down version of the Craftsman bungalow.

.

Four different eras of Vancouver residential architecture

.

….The second photograph neatly lines up houses from different periods of more recent Vancouver residential construction. On the left is a ‘late model’ Vancouver Special from perhaps the early or mid 1980s, when builders were dressing up the basic design with features like split roofs and upper storeys with offset sides, just before Vancouver City Hall put an end to the style’s proliferation. The other two houses you could call new-style Vancouver Specials, or monster houses (although I call them “mini monsters” because you can only get so big on a 33-foot lot), or the term I like best, from the general contractor who eventually completed our renovation: “builders’ boxes”. The house in the middle was probably built in the late 1980s, or early 1990s, when terracotta roof tiles, light yellow vinyl siding above a brick half-facade, and rows of narrow windows was a common look. The house on the right, although it looks similar to a number of houses built during the boom, was probably built in the mid 1990s. A clue that it pre-dates the boom by a few years is the colour — pink, which has now given way to beige as the one-colour-fits-all choice of discount spec builders — and the curved bay windows, with the stepped detailing beneath, which were common around 1994, if my research on RealtyLink is anything to go by. The trend over the past few years is boxed-out bay windows, with flat undersides that run straight back to the house wall.

.

Three eras of the Vancouver Special

.

The inventory results

Here are the results of my inventory. Over two days, I do a block-by-block count, take a few photos along the way, and quit when my feet get tired.

…• 60 blocks (the pocket formed by Commercial Drive on the west, Nanaimo Street on the east, East 1st Avenue on the north, and East Broadway on the south)

…• 130 new houses (prior demolitions assumed — or actually witnessed — although in a small number of cases a lot never before built on may have existed)

…• 100 major renovations

…• 78 minor renovations

…• An unknown number of ‘hidden renovations’ — all those shiny new kitchens and bathrooms, and mortgage-helping rental suites, that from the street give no indication of their presence (even when I try, unobtrusively, to look in people’s windows). I know of four major renos in the neighbourhood that fall into this category, and I record them, but undoubtedly many more occurred over the last eight years.

….I do the following calculation on adjusted figures: the total number of major renovations and new houses (204), divided by the number of blocks (51), divided by the duration so far of Vancouver’s real estate boom (8 years). I exclude partial blocks where I counted houses on the far sides of the main streets that form the boundaries of the pocket, and I adjust for double blocks (count 2), and blocks-and-a-half (count 1.5). The result is an average of 0.5 major renovations and new houses per block, per year — or one per block every two years. However, on the 23 most active blocks, each with an above average total number of projects (5 or more), the average is 0.77 per block, per year — or one per block every 16 months. One major renovation or new house per block every 16 months may not sound like a lot, but consider this. Using VanMap, the city’s web-based GIS, I count all the lots on every block in the pocket, and calculate an average of 23 lots per block. If the rate of change on the most active blocks were to continue unabated, the housing stock on these blocks would be completely renovated or replaced in 30 years. Based on the rate of change for all the blocks that I walked, the entire neighbourhood would be completely renovated or replaced in 46 years.

….Forty-six years ago was 1964, about a year before the earliest Vancouver Specials were built. From a statistical standpoint, if the rate of change in Grandview during the current real estate boom had been ongoing since 1964, the only house that would still exist in the first picture of older housing stock above, or be recognizable in its original form, would be the second one, the Vancouver Special. If we consider the elevated rate of change on the most active blocks during the boom, every house in the first picture would be gone, or renovated to the point of being unrecognizable. Grandview’s streets would be ruled by houses like those in the second picture above, and the newer ones in the photographs below.

….I’m sure there are people at City Hall and the Land Title Office with the appropriate databases who could do this number crunching and analysis much more efficiently and precisely, but my roughhewn results probably wouldn’t differ much from their more precise ones when it comes to an overarching statement. Grandview, and other Vancouver neighbourhoods currently experiencing rapid change, have been profoundly affected by the real estate boom.

.

My inventory map

.

You would recognize nothing

Imagine a residential street, say the one on which you grew up, with every last house renovated to the point of being unrecognizable, or demolished and replaced with a new house, in a 30-year period. Put another way, you could leave home at 18, and come back in early middle age, and not have the slightest inkling you were standing on the street where you grew up. You would recognize nothing. It’s possible this imagined scenario could become real in neighbourhoods all over Vancouver. The current rate of change strikes me as disorienting. I remember visiting Vancouver in the mid 90s while living elsewhere for a few years, and my disorientation coming across the Granville Street Bridge and seeing all the green glass Concord Pacific towers for the first time. Whoa! Where the hell did all those come from? As if a squadron of alien spaceships had set down on the north shore of False Creek.

….The rate of change in many parts of Vancouver in recent years doesn’t feel human scale, and I think if it continues unchecked for a generation, it would be a bad thing for the individual psyches, and collective psyche, of Vancouverites. You can’t be constantly destroying and remaking your home without it messing with your head. When you can’t count on recognizing things, can’t count on things as fundamental as one’s home and its various touchpoints remaining relatively reliable and stable, the danger is that you stop understanding that certain things have a value that isn’t solely calculated by the marketplace, that certain things, although they may seem mundane, are worth preserving. You may grow up as someone who feels his or her own personal history to be disposable. Why get overly attached to anything if it could be wiped off the face of the earth tomorrow?

.

The boom neighbourhood

Here’s a sample of renovated and new Grandview housing stock that in the last eight years has been replacing the old.

….The first shot is a row of four heritage-style duplexes — new houses designed to look like the more elegant of Grandview’s original single-family dwellings built a hundred years ago, and also designed to hide the fact that they’re front-and-back duplexes. The fifth house in the row is an actual old house. City Hall encourages new house design that fits in with the existing streetscape. Given the rate of change suggested by my inventory, and the amount of demolition, on many blocks ‘existing streetscape’ is more of a conceptual notion than a reality. A friend of mine calls these “faux heritage houses.” I tend to agree. Are they really just builders’ boxes with an overlay of ‘character’? Somewhat cynical insta-heritage designed to entice the Anglo-Saxon demographic priced out of the West Side? They feel like a simulacrum of the old designed to make some of us feel better about the fact we’re progressively destroying that which is actually old.

.

Heritage-style duplexes: one old house, and four new houses designed to look old

.

….The second shot is a good example of the other type of new house built in Grandview during the boom — the naked builders’ box that does little to disguise its essential box-ness. Towering over the two remaining stucco bungalows, which have so far escaped the excavator’s jaws, it’s hard to argue that these new houses fit in with the existing streetscape. But once those last two survivors from the 1930s or 1940s are gone, and replaced by builders’ boxes, a new uniformity will be established. I’ve come up with another name for this style of house: boom box. Builders’ boxes built during the boom.

….Aesthetics is a personal matter. I find these boom boxes ugly, but others may not. Or aesthetics may not be a primary concern when selecting a house. And unlike the new-age heritage houses, I don’t detect any cynicism in the forthright utilitarianism of these structures. Much like the original Vancouver Specials, these houses maximize square footage for the price, and they work well for larger families. In Grandview, and East Vancouver in general, these are often longstanding Chinese-Canadian families with working class origins, often with three or even four generations living in one house (as distinct from the more recent, wealthier immigrants from China gravitating to the suburban municipality of Richmond). If you have an aged mother, and two or more adult children living with you, you need space.

.

East Vancouver boom boxes: builders’ boxes built during the boom

.

….And finally, a before-and-after shot of one of those renovations that completely transforms the original house.

.

Before and after

.

Where’s the money coming from?

The answer to this question is simple. For homeowners undertaking major renovations or demolishing and rebuilding: from the houses themselves. For developers and builders constructing spec houses (houses built with the speculation of finding a buyer): from the killing they made on the previous spec project. Once the real estate boom gets seriously underway in 2002, and prices keep cranking upward, the boom becomes self-sustaining to a certain degree. Owners of existing homes see their annual property assessment balloon, as if on steroids. After three or four years of these eye-popping increases they start to feel wealthy, and the bank agrees. Interest rates keep falling. In the aftermath of 9/11 rates fall to generational lows. In the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, interest rates hit all-time lows. Over the past eight years, cheap money, and then incredibly cheap money, drive house prices into completely new territory — surreal territory in Vancouver, where many homeowners sit on increasingly massive war chests of home equity. Yes, it’s paper equity. Yes, it would shrivel in the event of a price collapse. But it’s paper wealth that’s solid enough for the banks to approve large home equity lines of credit secured by the houses, like the one my wife and I are given when we renew our mortgage in September of 2006.

….For many Vancouver homeowners, armed with these HELOCs, or with construction loans, it’s been time to spend. For builders, developers, and the various construction trades the only problem is the inability to clone themselves so they can take the money and complete the projects twice as fast, the demand is so great. Renovations that completely transform modest houses, often coming close to doubling the square footage. Tear-downs to make way for ‘dream homes’. Tear-downs to free up land for spec building, which can be more lucrative than custom building for a specific client. There’s no mystery about what’s at the root of the recent dramatic changes in Grandview, and in many other Vancouver neighbourhoods. It’s money.

….And, in many cases, the changing demographics associated with the money. The willingness to spend it. The longstanding blue-collar inhabitants of Grandview, the retired Italians, and Portuguese, and Chinese, the widows, are sitting on the same home equity as the more recent, white-collar arrivals, but they aren’t spending it. In fact, they’ll be sitting on even larger cash mountains, because they paid off their modest homes years ago. One hundred percent ownership. But these older residents achieved that ownership through years of grinding it out in tough jobs, and through financial prudence — like my wife’s parents, living a few blocks away, working nights in various restaurant kitchens, and the early shift in a meat packing plant. Scrimping, saving, keeping a lid on unnecessary expenditures. These are people constitutionally averse to dropping five or ten grand on granite countertops, or stainless steel kitchen appliances. (Will events in the coming years cause all of us to become constitutionally averse?) They’ve lived in their houses for years. They’re used to them the way they are. They aren’t interested in the stress and upheaval of a major reno. They’ve got the equity, but they need it to backstop their retirements, and to pass on to their adult kids.

….It’s the more recently arrived inhabitants, with years of earning potential still ahead, who are spending. White-collar information professionals who work their days at computer keyboards are supplanting blue-collar workers who needed to move all day long, use all the muscles in their bodies to earn a living. A younger generation, with English as their first language, and their labour more valued by society. Some of the new arrivals are real estate refugees from the West Side, where they may have grown up, or where they might have been able to buy in previous decades, and perhaps still aspire to live one day, and where the average house price is currently 1.5 million dollars. The new influx has a different relation to money, and debt, and the rapidly changing built environment of the neighbourhood is a direct manifestation of that relation.

….I’m going to leave discussion of whether or not Grandview is gentrifying to a future episode. Certainly, some of the elements of gentrification appear to be in place, but a number of local subtleties prevent a simple answer to the question.

.

Shock and disorientation

Most of us have experienced the shock and disorientation of returning to a familiar place and finding it radically changed — never more so than if the familiar place is a house in which we grew up, and upon returning, anticipating that first sight, the feeling of reacquaintance, we find it gone. A bald, empty lot stares at us, or some new monstrosity. Something new always seems a monstrosity in our eyes. The alteration from the image in our mind, the feeling in our heart, at the very least feels like a breach of trust, and depending on how calamitous the circumstances, a violation, a kick that leaves a sick feeling in the gut. So imagine coming back to the familiar place and finding the entire block, every house, gone, or so changed that the block, the houses, might as well be gone. The one-time connection to you is certainly gone. Part of your personal history is effaced.

….There’s something very personal about demolishing a house, a home. It’s not the same as dynamiting an aging sports stadium. People can feel very strong connections to public structures, but they’re part of a communal connection. The spectacle of a half torn apart home is like a personal nakedness come upon, always a little unseemly. The emotions, the personal history, the tender or fraught relationships that the house has contained, and concealed, and protected from view, are rudely exposed. Like ghosts escaping into the ether, the long-hidden truths of past lives, having seeped into the walls over decades, now evaporate when exposed to air.

.

Some East Vancouver ghosts

We don’t demolish our house. We renovate it to a degree that would certainly fit with my definition of ‘major’, with a final phase of the renovation still in the future. In hindsight, the financial wisdom of our choice may be questionable. For perhaps a third more money than we’ll end up spending once all phases of the renovation are complete, we could have demolished the house and built a new one. One with a full-height ground level, more square footage on the main floor, and a second storey that might afford a view of the mountains, at least when the leaves are off the trees in winter. And an increase in market value that could very well surpass the extra outlay upfront, although this last point is debatable, and dependent on what happens to house values in the coming years. But these are things you learn with experience.

….What I do know is that some ghosts would have been lost forever if we’d brought in the excavator and the forty-foot dump trailer and smashed everything to kindling.

.

Homemade wine

The first ghost is a remnant from a wooden box of Zinfandel wine grapes — the box end with the producer’s colourful label. I find this board when I’m disassembling the framing of the bathroom in the old rental suite. Nailed between two studs, it’s serving as a piece of blocking for the shower plumbing. So along with their spouses, one or both of the Portuguese brothers, who put in the old suite in the 1980s, were probably makers of homemade wine. I know from my neighbour that the family used to run a bakery on nearby Nanaimo Street.

.

Wine box end

.

War bride?

The second ghost is fragile, a 3-inch by 4-inch scrap I find beneath attic insulation, a paper label clinging to the back of a board that along with a few other boards has been used to close off an attic hatch. The label says NOT WANTED, and a woman’s name is typed on it: Mrs. D.O. O’Malley. Although this ghost is the most recent I’ve encountered, it’s the oldest.

.

Not Wanted label

.

Some older readers may understand immediately the original purpose of this label, but it takes me a while to figure it out, and without Google, I might still be scratching my head. I assume “8/51” in the lower left corner is the date August 1951, which means the label comes from a time when immigrants arrived in Canada by ship, rather than aircraft. “Not Wanted” is short for “Not Wanted on the Voyage”, a designation given to things like steamer trunks and wooden crates that traveled in a ship’s hold because the passengers didn’t need them during their time at sea. Googling key parts of the address in the lower right corner — Canadian Civilian Repatriation Section, Sackville House, London, W.1 — unpacks the rest of the story.

….The Civilian Repatriation Section was part of the Canadian Wives’ Bureau, a department of the Canadian military set up in England and Europe to transport war brides to Canada where they were reunited with the returned servicemen they’d married during the Second World War. So Mrs. D.O. O’Malley may have been a war bride , although 1951 is late for a Canadian war bride. Most traveled to Canada in 1946, the year after the war ended. But the fact that it’s a woman’s married name that appears by itself on the label certainly suggests a war bride. And our house, a modest bungalow built in a working class part of town in 1946, certainly fits well with the theory of O’Malley the returning veteran, buying or building a new little house to bring his bride to. Somewhat inconclusive, but I’m happy to let elements of the mystery remain, at least for now.

.

Childhood home

The final ghost is flesh-and-blood, and on a bright summer day rings the doorbell. Peter Chang is about my age and he tells us that he was in the neighbourhood and our house is his childhood home. We invite him in and give him a tour, or more accurately, he gives us a tour of the ghost house that hovers in his memory, superimposed on the one we’re all standing in. Peter is surprised by the attractive Douglas fir floors, probably the best feature of the house, which we had refinished just before moving in. The brothers (I’m assuming it was them) had previously butchered them, a do-it-yourself attempt at refinishing that left waves, and divots, throughout. Some things really should be left to specialists. But Peter had not even been aware that there were original fir floors. When his parents bought the house in the late 1950s, the wood had been entirely covered with battleship linoleum, and it stayed that way throughout his childhood and teen years.

….We spend an interesting hour listening to Peter’s details about the house and his family. They were the first Chinese family on the block. His father was no longer alive, and we get the sense he may have died prematurely. At a certain point Peter and his family had to ask the neighbours to stop giving his father bottles of their homemade wine. As I’d suspected, there was previously a set of stairs to the lower level, in the back corner of the house where there’s now a narrow bedroom on the main floor, and the laundry room directly beneath. As part of putting in the rental suite, the brothers obviously removed the stairs, and closed the opening, gaining a small room on each floor in the process. Peter and his brother used to go down this U-shaped stairway to the partially finished basement, where they spent hours with their chemistry sets. Until Peter mentions it, I’d totally forgotten about those childhood chemistry sets. The concrete front steps on the house were put in by Peter’s parents when the old wooden ones started to rot and became unsafe. The bright red that peeks through several layers of peeling and flaking grey paint is the original colour that the stairs were painted.

….We get Peter’s contact information. He tells us he has quite a few photographs we might find interesting. We intend to get in touch, although we haven’t yet. Peter’s visit is prior to our renovation, so if he comes back for another look, he’s going to be surprised again. But if we had demolished Peter’s childhood home, would he have had any reason to ring our doorbell, or the heart to?

.

February 2010, Grandview

.

.

Next episode

Part 6: “Renovation Nervosa”

I don’t always walk the blocks of our neighbourhood purely in the spirit of unscientific inquiry, as I do in February of 2010, when I count all the renovations and new houses. In our first years in the neighbourhood, as it starts to transform before me, I often feel not exactly envy, but anxiety that other people are getting on with things and we aren’t.

.

Financial details

.

.

From 2004 onward, all mortgage and LOC balances are as of 31 December of the year in question.

.

2003

Asking Price: $355,000

Sale Price: $355,000

Down payment: $88,750 (25%, ergo, no CMHC insurance, representing thousands of dollars of additional cost)

Mortgage (at purchase, Sep 2003): $266,250

Terms: 3 year fixed at 4.00%, 18 year amortization, bi-weekly payments

2003 Property Assessment (estimate of market value on July 1, 2002): $260,600

2004 Property Assessment (estimate of market value on July 1, 2003): $330,500

Equity based on assessment: $64,250

.

2004

Mortgage principal: $247,330

Terms: 3 year fixed at 4.00%, 18 year amortization, bi-weekly payments

2005 Property Assessment (estimate of market value on July 1, 2004): $420,000

Equity based on assessment: $172,670

.

2005

Mortgage principal: $201,829

Terms: 3 year fixed at 4.00%, 18 year amortization, bi-weekly payments

2006 Property Assessment (estimate of market value on July 1, 2005): $461,000

Equity based on assessment: $259,171

.

2006

Mortgage principal: $191,884

Terms: 5 year variable at Prime minus .75%, 25 year amortization, bi-weekly payments

HELOC balance: $4,291

HELOC interest rate: variable, at Prime.

2007 Property Assessment (estimate of market value on July 1, 2006): $570,000

Equity based on assessment: $373,825

This is brilliant. Thank you, Froogle Scott!

I’m in Marpole and there are 2 rebuilds or major renos happening per block on the 10 block route I walk every day. I think Marpole is late to the party but is trying to make up for lost time: I wonder if I should do an inventory as well!

My heart broke in early November when a gorgeous 40s build was crushed to splinters to make way for a Boom Box – I’d seen it go on the market and had hoped for its rescue…

A chilling anecdote of how both housing starts and major renovations have increased living space far above what the population can absorb.

If you want to see turnover, drive through Kerrisdale. The neighbourhoods are literally unrecognizable from 25 years ago.

space889 posted a comment regarding this episode at vancouvercondo.info 26 Feb 2010 10:52 am –

Excerpt:

“While I certainly feel the sentimental feelings the writer has for his old neighborhood and how he wish things don’t change so much and in his view for the worse, I must say I don’t feel quite the same way. I had recently gone back to my first home in Mount Pleasant when I came as an immigrant back in 1989 and lived there for about 10 years. There has been a lot of changes to the neighborhood and blocks where I don’t recognize where I am. There have been large heritage style houses torn down and rebuild as a large townhouse complexes. However to me this is also progress. While people maybe nostalgic about those cute character houses building pre-1930, or those cute charm wartime bunglows, the question I have is do they really think it’s a good idea to keep all those houses as they are, never renovate or rebuild them? I think we should preserve some heritage buildings but that doesn’t mean all new developments are bad. Some are, some aren’t. However to to me wishing things don’t change is even worse.”

For the full comment, see link above.

I don’t care if people paint over interior woodwork, and I don’t get sentimental about houses getting torn down.

But, I do get sad when houses are neglected and falling apart. It’s so wasteful that for want of a few roof patches and coats of paint on the exterior, a house will be left to rot in the Vancouver rain. Big houses, little houses, monsters or antiques, I’m happy if they’re not falling over. A few bucks in prevention could save so much!

Our house turns 100 years old next year. Yay house! The landlord does as little as possible, as late as possible, but she’s still standing, for now.

not only did you save the memories by renovating instead of razing, you also saved the cost of renting while razing – surely that would make a big difference to the relative costs? We live in a replacement house – the former one on the lot burned down – so no old mysteries for us to stumble upon.

Great piece, Froogle Scott. Resonates with me, as they say. In Abu Dhabi, people demolish tower blocks after 10 years and build taller towers, with more flats in them. One reason: the owners are the sons of bedouin, now in late middle age. Here, historically, there were no, or only a few permanent dwellings. When you had used up a place, you broke camp and moved on, leaving the mess behind. So if you can fold up a tent, you can knock down a building. Nothing is permanent, except the desert sands where you sit on the weekend and eat barbecued goat with the family, next to a 4X4. Wilfred Thesiger said in The Arabian Sands “The closest thing they have to architecture is stones piled together to make a fireplace”. My local coresidents, sons of the sons of bedouin, are starting to preserve their grandparents’ mud houses out in the villages, realising that there are ghosts there.

You get into some rather deep territory with the “ghosts” theme, but I would give it full marks for perception. Having the ability to appreciate a house for its ghosts is probably rare, but speaks of an awareness of the idea of permanence, community, family and a kind of handed-down tradition. I would actually not use your word “ghosts” for what you found or sense you have found in your house. I would rather use the word “lives”, or “the living”, because ghosts is what you will have left when all of Vancouver, barring your modest Grandview dwelling, has been torn down and replaced with boom boxes.

Thanks for the discussion, Peter Barlow.

The boom boxes and other newish buildings in Vancouver have little potential for the patina that comes with human touch and use. In older buildings, in many cities, one sees this polished effect on wood, on stone, on brick. The trace left by the people that have come before us. Metaphorical ‘ghosts’, if you like. It’s an effect that enhances the value of both objects and people.

Now, in Vancouver, dry-wall gets grubby, or laminate peels, and it’s replaced after an afternoon drive to Home Depot.

Even roofs are built with just 25 years of life span!

Pingback: Home Depot Nanaimo Bc | Home and Design Interior

Pingback: IHB News 3-6-2010 | Irvine Housing Blog